Innovation

This carbon fibre alternative went from ski slopes to Formula 1 circuits

by Samarth Kanal

7min read

It seems like carbon fibre is everywhere in motorsport. It’s present in single-seater racing cars from Formula Regional to Formula 1, sportscars across multiple disciplines and even safety gear. But now there’s a natural fibre that can be used to bolster or even replace carbon fibre.

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

Swiss firm Bcomp uses flax fibres to produce stiff fabrics that can replace or reinforce carbon fibre on racing cars. Furthermore, it uses flax to create a grid inspired by leaf veins that can reinforce its own technical fabrics or be used in a hybrid format with carbon fibre.

Natural fibres provide manufacturers with a range of benefits, including safety and aesthetic, while also being sourced naturally.

While this technology has been used in F1 among other championships and series, it was born in a very unlikely setting.

Made in the mountains

Bcomp’s story began on the ski slopes of Switzerland where the company’s founders, passionate skiers, sought to build a high-performance ski core combining balsa wood and flax fibres.

Material scientists from the EPFL (Ecole Polytechnic Federale de Lausanne) Technology Institute in Switzerland discovered that flax fibres possess exceptional properties, particularly when it comes to bending stiffness.

Natural fibres can even be used in road car interiors. The dashboard and interior trim within the Kia concept EV2 is made from a composition that includes natural fibres

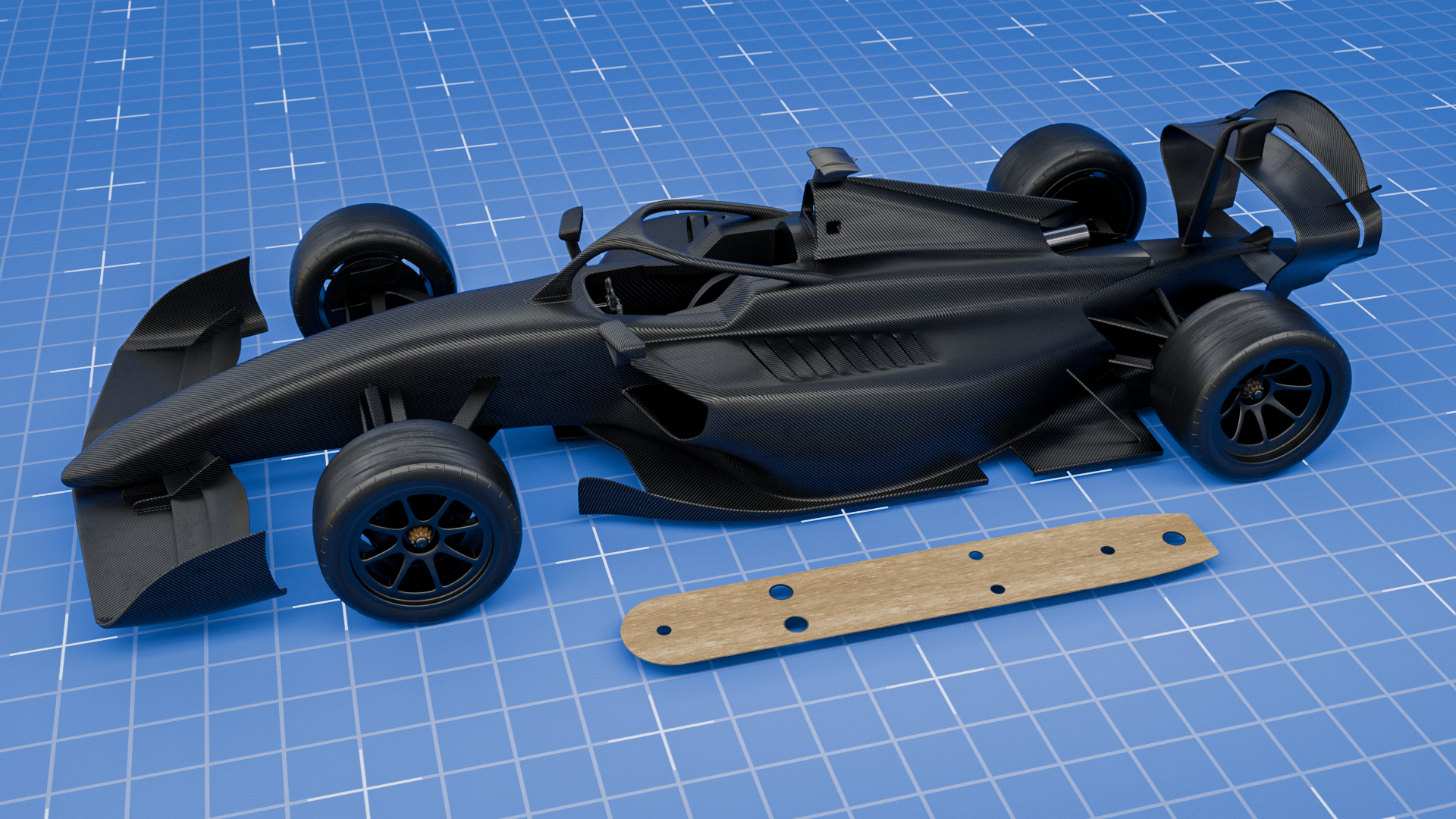

That led to the development of a technology called ‘powerRibs’. Inspired by the structure of leaf veins, this is a flax-fibre-reinforced grid in a 3D structure that can then reinforce carbon fibre or flax fibre, decreasing overall weight and cost.

This innovation took the company away from skis as it shifted its focus to the wider opportunities in automotive, aerospace, transportation and motorsport applications.

“Motorsport is super interesting, because the mental barriers to try and use [new] things can be very low. Engineers like to use new stuff; it can take just two weeks from an initial conversation to implementing a new technology,” says Bcomp’s Business Development Manager Johann Wacht.

“It’s quite a good [business] environment for a scaleup like us.”

In 2017, the company presented… a natural fibre monocoque - the first of its kind - that debuted at major motor shows in Frankfurt and Paris. Shortly afterward, the collaboration with Porsche Motorsport kicked off a “super crucial development partner” phase, resulting in the introduction of Bcomp’s natural fibre technologies in the Porsche Cayman GT4 CS sportscars in 2019.

Natural fibres visible on the bonnet of a Porsche Cayman GT4 sportscar

Natural fibres in F1 and other motorsport

After Porsche adopted the material, McLaren began using natural fibres in its F1 seats.

Lando Norris used a seat composed of natural fibres, while Daniel Ricciardo and Carlos Sainz used F1 seats composed of a hybrid between natural and carbon fibres.

The material has also found its way to Formula E as BMW adopted flax fibre in its Formula E car’s cooling shafts.

In sportscar racing, today more than 10 manufacturers are using natural fibres to replace or reinforce carbon fibre. Wacht found adoption within a company would spread once it was tested in a motorsport setting.

“BMW used it in Formula E, then they moved to using it in DTM [German touring cars], then they moved to GT4, and now we are in pre-development to bring the materials to its road-going sportscars and in large-scale mobility,” he says.

McLaren Formula 1 driver Lando Norris examining his natural fibre racing seat

As for current F1 teams, competitive sensitivities mean Bcomp can’t disclose who is using its fabric and strengthening technologies, but it’s understood that two teams are using it as of 2025.

Super Formula, which is a high-level Japanese single-seater series, uses the material in abundance - while the Super Formula-derived A2RL Artificial Intelligence racing cars also use it.

“These cars are now racing with a natural fibre sidepod and engine cover and you can see that they use carbon fibre as a spine to lend structural rigidity, and everywhere else they use natural fibres,” says Wacht.

He adds that GT4 sportscars even use a fully natural fibre bodywork, given that specification’s temperature, rigidity, and structural requirements are closer to road cars.

Is this a replacement for carbon fibre?

Flax fibres aren’t always a replacement for carbon fibre, as Wacht explains.

“Carbon fibre is superior in terms of strength compared to natural fibres, so when you use carbon fibre compared to high-performance natural fibres, flax in our case, carbon fibre is much stronger.”

He says bending stiffness is the “technical sweetspot” that demonstrates the viability of natural fibres.

The interior of the BMW M4 GT4 racing car with Bcomp natural fibres visible on the centre console

In the case of F1, carbon fibre honeycomb is layered between plies of the material and Wacht admits that this is the strongest way to go about building a carbon fibre body part.

However, this is a costly approach and, in the case of sportscar racing, monolithic carbon without core structures - just multiple layers of carbon fibre - is used.

“It’s here where we can replace carbon [with a material of similar properties] and have a material that is way safer; when you break a natural fibre part, the fibres are blunt and you don’t risk cutting your hand or something similar.”

Wacht says he’s not looking to phase out carbon fibre but to add an alternative that could enhance safety.

Natural fibres visible in Lando Norris’s McLaren Formula 1 racing seat

Natural fibres in road car manufacturing

For road cars, the approach to using carbon fibre or natural fibre differs from motorsport applications.

Interior components use thermoplastic systems (polypropylene) rather than high-performance epoxy resins (as polypropylene is easier to use en masse), supporting recyclability through grinding and reinjection moulding.

If natural fibres are used in interior materials, Wacht says this could form “a fully circular part” - one that can be used repeatedly.

However, Bcomp has noticed that the colour of its natural fibres - an earthy brown - might not be the most aesthetically pleasing aspect of it, which is why it’s developing coloured versions of its flax fibres and bespoke weave patterns to suit the needs of different manufacturers.

The only colour Bcomp might refrain from using is black, and that stems from decades of conditioning.

BMW is exploring the replacement of carbon fibre plastic parts with natural fibres

"People are so nudged to the point that you see something that is black with that structure that many people say, ‘yeah, it's carbon fibre’,” says Wacht.

"A lot of people don't really recognise that these are natural fibres.

“What we are developing with the [manufacturers] is that they have their own high-performance natural identity. That in the future a fan says, ‘OK, that's not carbon, that's BMW, that's Porsche’.”

Dyed materials can also provide a slight benefit in terms of weight while maintaining stiffness. Wacht says that a 245 GSM (grammes per square metre) dyed material performs similarly to 300 GSM natural material.

As the motorsport industry grapples with efforts to improve sustainability, natural fibres offer another potential option as they maintain the performance standards of carbon fibre while offering the potential to reduce carbon emissions.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

/enhanced_resized_image_1920x1080.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)