Motor

How the V10 engine came to rule Formula 1

by George Wright

8min read

Recent but fleeting news that Formula 1 may consider returning to V10 engines in the future sparked excitement over a return to the era of screaming power units.

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

For some, a return to the symphonic allure of F1 in the 1990s and 2000s is welcomed; others are tentative as they point towards the current hybrid power unit’s remarkable thermal efficiency (above 50%) in producing more than 1,000 horsepower and taking F1 cars to speeds of more than 220 miles per hour.

Whichever side of the debate you fall upon, the discussed return of V10s to F1 after a two-decade absence does beg the question: How did V10s become Formula 1’s engine of choice, and why did the sport then end up abandoning them?

McLaren (centre) and Williams (R) were the only two teams using V10 engines in 1989

The early years of V10 engines

It’s often forgotten that V10 engines are a relatively recent development in F1.Despite the early years of the sport featuring engine designs ranging from petite straight-four units up to behemoth H16 powerhouses, V10s did not feature even once in the sport’s first three decades.

Designers of the period were concerned about vibrations arising from the odd number of cylinders (five) per bank in a V10 engine and therefore chose to avoid the layout entirely in favour of less complex V8s, or V12s, which were only marginally more complex than a V10 while having fewer vibration concerns and a similar power output.

This situation finally changed following a bombshell announcement by the FIA in 1986. After a year or so of rumours, it finally confirmed its intention to phase out the then-current 1.5-litre turbocharged engines by 1989, in favour of naturally-aspirated 3.5-litre units.

The turbocharged F1 era was exciting but often explosive - as illustrated by the Lotus 98T driven by Ayrton Senna in 1986

As it happened, just prior to the FIA’s announcement, two German engineers called Fritz Indra and Gert Hack had published a book on Formula 1 engine design. Therein, they calculated that for an engine displacement of approximately three litres, an optimised V10 should theoretically produce only 1.8% less horsepower than a similarly optimised V12, while conferring substantial packaging and weight advantages which would more than make up for this slight difference in power.

They likewise determined that the vibration issues which had kept designers away from V10s for so long would be within acceptable tolerances provided an appropriate bank angle between the two sets of cylinders was selected. Based on this evidence, it seemed that V10s could be ideal for 1989’s new engine paradigm.

Alfa Romeo was among the first to put Indra and Hack’s theories to the test, designing a V10 engine intended for Formula 1 in 1985 for the following year (though it would never be raced following a falling out with the Ligier team it had been intended for).

The mantle of heralding the start of the V10 era was therefore taken up by Honda and Renault instead, both of whom had been prominent manufacturers during the previous turbo engine era and each of whom settled upon a V10 design to take them forward into F1’s new era.

McLaren clinched the 1989 drivers’ and constructors’ championship with its Honda V10 engine

Of the two manufacturers, Renault’s RS1 engine was in many ways more advanced than its contemporary, notably featuring pneumatic valve springs similar to those seen in modern F1 engines. This allowed its engine to achieve higher rev limits by enabling the valves to retract more quickly, in turn preventing them from colliding with the cylinder heads.

Honda’s engine was less cutting-edge by comparison, with conventional spring-operated poppet valves and a counterweighted balance shaft which helped to cancel out engine vibrations, but which also added weight to the engine.

Despite their differences, both Honda and Renault’s engines proved extremely competitive right out of the gate. McLaren-Honda won 10 of the 1989 season’s 16 races on the way to the championship, while Williams-Renault claimed a further two victories.

It wasn’t all plain sailing, however. While McLaren-Honda would repeat its championship success in 1990, that season also saw a concerted challenge from the V12-engined Ferrari 641. As it turned out, for an engine of 3.5 litres rather than the 3-litre unit modelled by Indra and Hack, V12s could still achieve substantially higher power outputs than a V10, enabling Ferrari and its V12 to run McLaren extremely close for the championship.

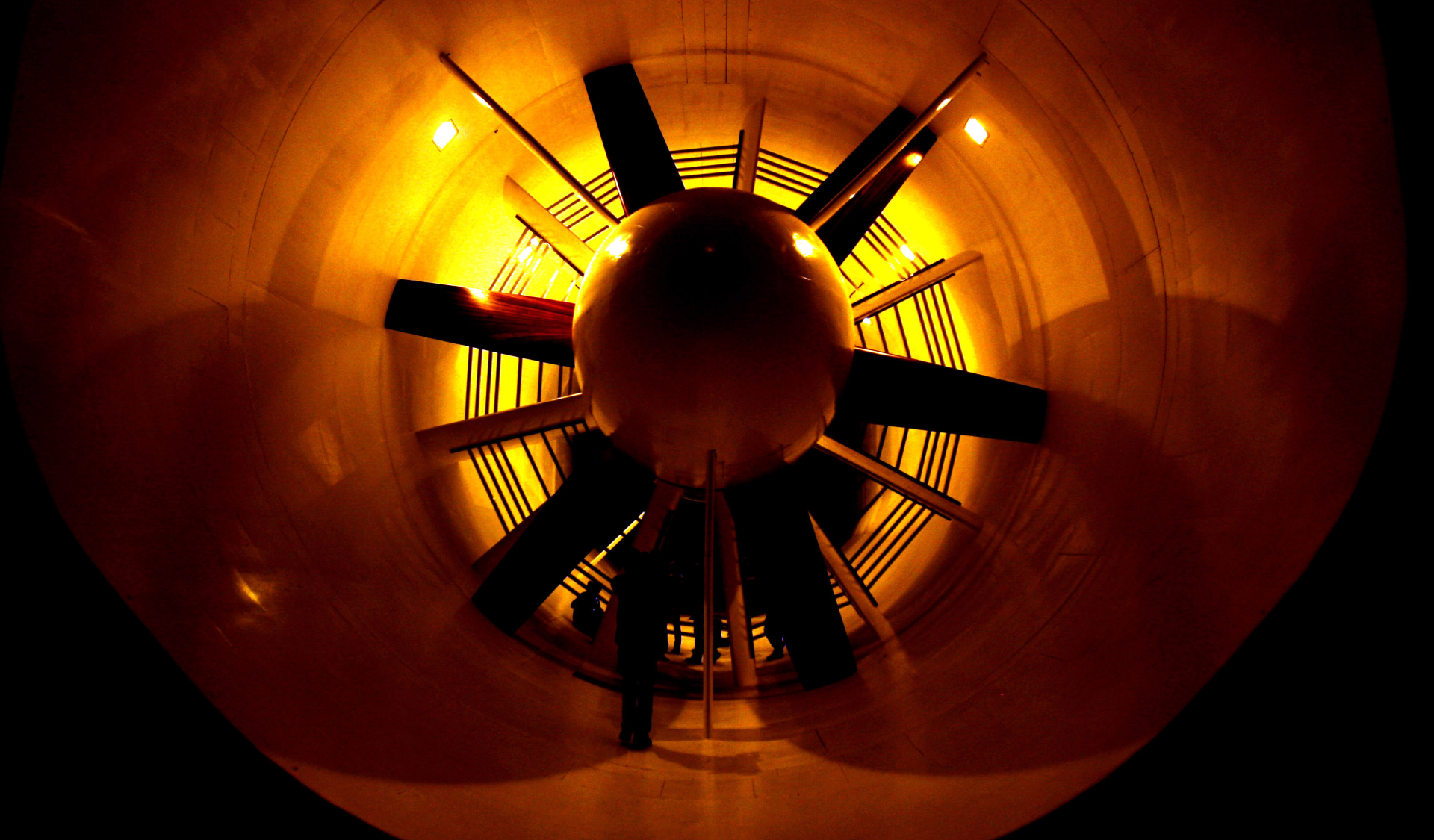

The 1990 V10 Honda F1 engine - deconstructed in the image above - took McLaren to the top that year once again

Honda in particular found this potential for extra power irresistible, and chose to abandon its V10 programme for 1991 in favour of a V12. This new V12, paired with McLaren’s MP4/6 chassis, duly won both world championships that year, showing that V10s were not quite unassailable at the front of the field just yet.

Renault responded by producing a new RS4 version of its engine, which produced a full 50 horsepower more than its predecessor.

The Williams team whom it supplied also introduced engine mapping software and therefore brought traction control to F1 for the first time by cutting ignition to specific cylinders in the V10 when wheel speed sensors detected the tyres were slipping.

With such technological leaps, the era of V10 domination began in earnest. Williams-Renault and its V10 powerplant won four consecutive constructors' titles from 1992 to 1994, though the Ford V8-engined Benetton driven by Michael Schumacher did manage to snatch away the 1994 world drivers’ championship.

Michael Schumacher won the 1994 drivers’ championship in his Ford V8-powered Benetton (L) but Williams took that year’s constructors’ championship with its Renault V10-powered car

The V10’s decade of F1 dominance

Prospects for V10s would only get rosier in 1995, as the FIA announced that engine displacements would be dropped from 3.5 litres to 3 litres. This was in response to the spate of accidents which had punctuated a tragic 1994 season, but also happened to align more closely with the optimal V10 configuration which Indra and Hack had theorised a decade earlier. It seemed the days of V8s and V12s were truly numbered.

Honda was no longer around to take advantage of this change, having left the sport after 1992, though it maintained a presence in the form of its Mugen subsidiary. Renault too would not stick around for much longer, withdrawing works support for its engines after the 1997 season was over.

Other marques were all too happy to take up the position of innovation which Renault and Honda had vacated. Manufacturers such as BMW and Toyota would soon join the sport, while the likes of Mercedes and Ferrari (who finally switched to V10s from 1996 after attempting to soldier on with a 3-litre V12 in 1995) also rose to the forefront.

With so many manufacturers in the field, and all having recognised the advantages of V10s by 1998 the engine development war intensified, with rev counts and horsepower figures climbing ever upwards.

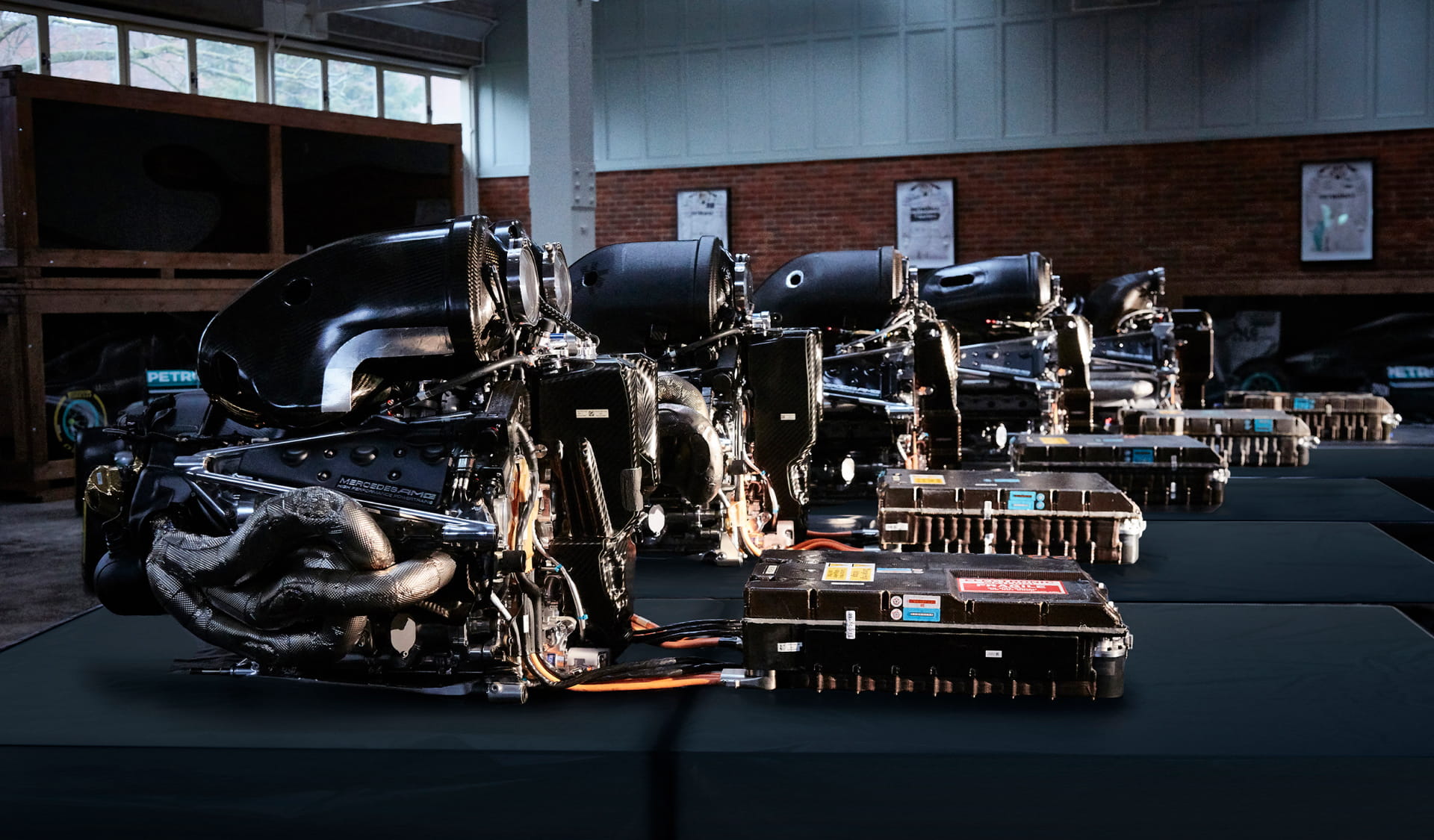

The cockpit of the 1998 V10 Mercedes-powered McLaren MP4/13

One key innovation was the introduction of beryllium-aluminium alloy pistons by Mercedes in 1998.

Manufacturers of F1 engines had long grappled with trying to balance piston stroke against rev count. An improvement in either of these variables could yield more horsepower, but increasing one typically meant decreasing the other, as having both a long stroke and high RPM placed an incredible amount of strain on the pistons, which was too great for conventional materials to handle.

By using beryllium alloy, Mercedes was able to get the best of both worlds. With a stiffness-to-weight ratio 3.8 times that of steel, it was strong enough that Mercedes could match the 17,000 RPM rev limit of its rivals while also attaining a longer piston stroke - a guaranteed ticket to more horsepower.

The resultant engine comfortably attained 800 brake horsepower, and powered the McLaren team to two consecutive world drivers’ championships in 1998 and 1999.

Mika Hakkinen won the 1998 and 1999 Formula 1 drivers’ championships

Beryllium was banned in 2001 following protests from Ferrari, who pointed out that Beryllium is a carcinogen and therefore posed health risks during the manufacturing process.

Despite these restrictions, power outputs continued to rise, and new developments were still brought forth. Among those making waves in the increasingly manufacturer-dense F1 engine landscape was Renault, who returned to the sport as an engine supplier for the Benetton team in 2001 ahead of its full takeover of the outfit the following year.

Renault’s new engine had one particularly notable feature. While almost all rival teams had used V10s with a bank angle of between 65 and 90 degrees to minimise vibrations and enable compact packaging of the rear of the car, Renault instead opted for a wide 111-degree bank angle. While this made the engine wider, it also lowered its centre of mass, and in turn the centre of mass of any car equipped with it, theoretically aiding handling. It was this engine with which Fernando Alonso took his first grand prix win in 2003.

Renault would eventually abandon its 111-degree bank angle in favour of a 72-degree angle, as Honda had used back in 1989. However, it did appear that there was some merit to Renault’s thinking, as almost all manufacturers eventually settled on an intermediate 90-degree bank angle due to its benefits to centre of gravity.

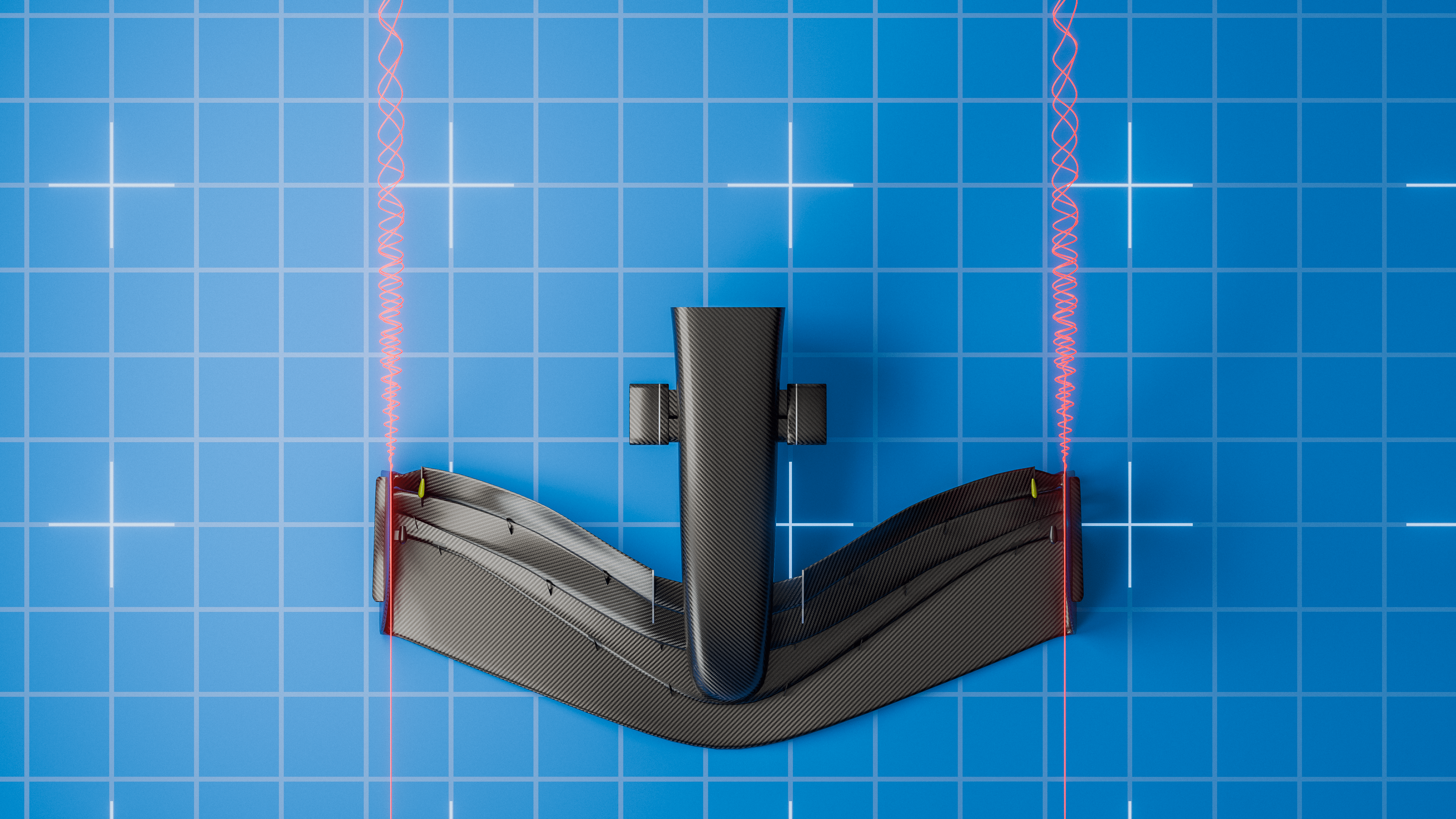

A top-down view of the Renault engine that took Fernando Alonso to fourth in the 2004 drivers’ standings, before he clinched two titles with the team

The end of the V10 era in F1

Despite all the money and the innovation, the V10 era could not last forever. In many ways, it was the expenditure and ever-increasing power outputs brought about by the development war which put paid to those screaming power units of the early 2000s for good.

The FIA grew increasingly concerned about the engine situation in Formula 1 as the 2000s progressed. Power figures were edging closer to the 1000bhp mark, which hadn’t been seen since the height of the turbo era in 1986, and teams were burning through several engines per race weekend in their pursuit of an advantage over rival manufacturers.

With complaints about the cost of the sport and environmental concerns growing louder as the decade progressed, the FIA was forced to take action.

First, it introduced measures to try to curb manufacturers' almost reckless pursuit of performance, mandating in 2004 that engines must last a full race weekend, before extending that to two race weekends the following year. More direct measures to reduce power outputs were also taken, with 2005 introducing rules limiting engines to a maximum of five valves per cylinder.

These measures ended up mattering little. For one, because top engines such as BMW’s P84/5 still comfortably achieved 19,000 RPM and over 950 horsepower in race trim even after the changes.

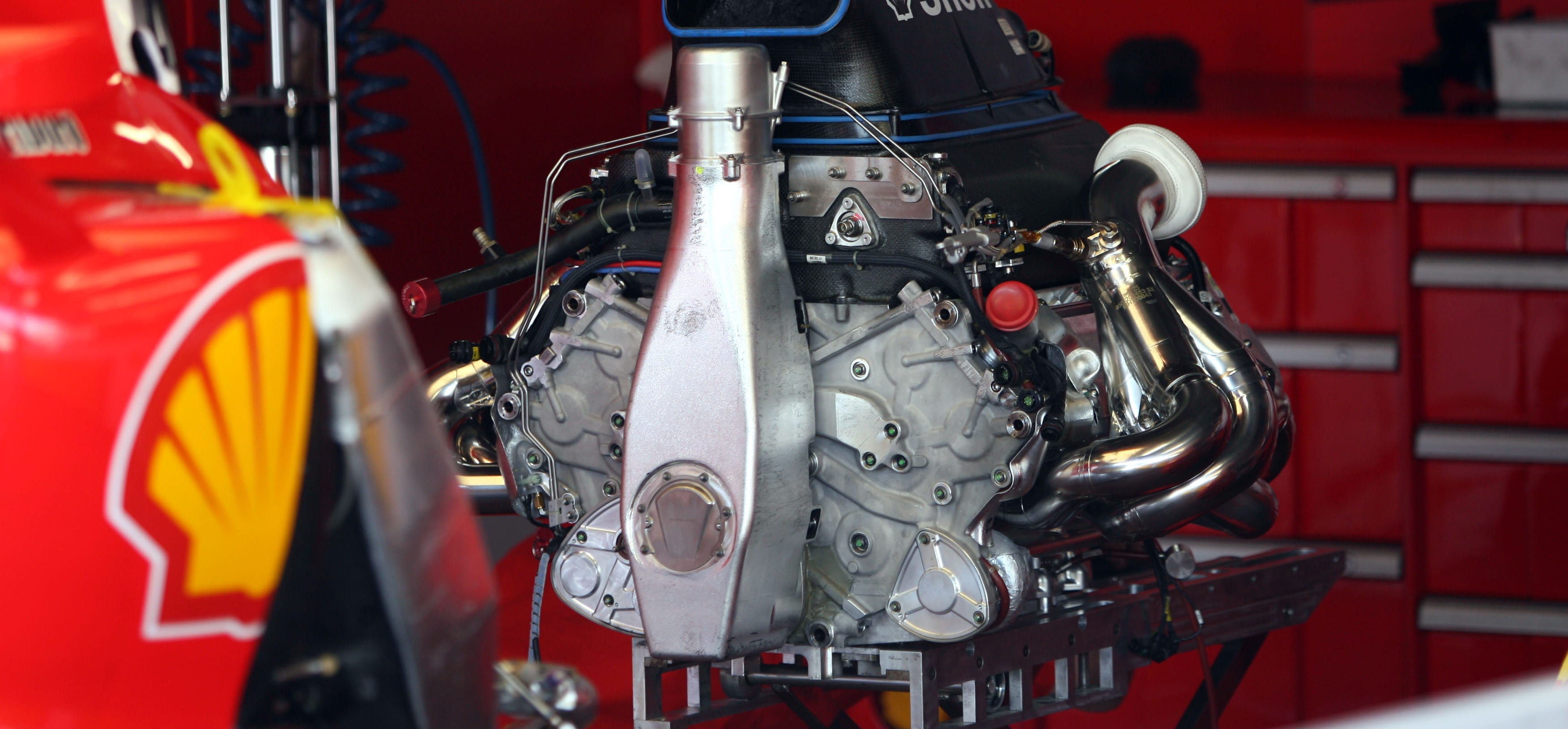

The V10 era came to an end in 2006 with V8 engines implemented. Pictured is the Ferrari V8 that powered the 248 in 2006

More pertinently, by the time the 2005 regulation changes came into force, the momentous decision which would bring the V10 era to an end had already been announced. From 2006 onwards, F1 would switch to 2.4-litre 90-degree V8 engines in an effort to reduce both cost and the speed of the cars.

V10s did get one last farewell fling, with Red Bull’s newly-purchased junior team Toro Rosso obtaining special dispensation to run with rev-limited V10 engines for 2006 only for cost reasons.

In early 2025, the FIA assessed a return to V10 engines as early as 2028 or 2029, but a meeting with F1 and key stakeholders in April 2025 put those plans to bed - for now.The return of V10s is still not quite out of the question, however, and there’s still a chance that F1 fans craving the sound of a field of wailing 10-cylinder monsters could get their wish after 2030 - but V8 engines have now entered the discourse.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)