What does it feel like to be an F1 driver in a ‘heat hazard’ race?

by Jack Cozens, Samarth Kanal

7min read

What if you could simulate the stifling humidity and searing heat that Formula 1 drivers face without travelling thousands of miles and jumping behind the wheel? We did exactly that.

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

Drivers undergo extreme training to ready themselves for the toughest F1 races which, in 2025, were officially designated ‘heat hazard’ races.

To prepare, F1 drivers might don multiple layers of clothing in the gym, or run on a treadmill inside a sauna to acclimatise to the heat and humidity.

The University of Roehampton in London, UK, takes a more scientific approach to simulating hot conditions. Inside its sports science department is a heat chamber.

This equipment is used by athletes across numerous disciplines such as tennis and offroad racing and McLaren’s F1 driver Oscar Piastri is one of its regulars.

McLaren F1 driver Oscar Piastri has used the heat chamber at the University of Roehampton in London

What is the heat chamber?

The heat chamber at the University of Roehampton is a small room in which heat is constantly channelled in to replicate an environment.

Additionally, moisture is added to the room to increase humidity.

So useful is this chamber as a controlled environment that even firefighters use it to emulate the hottest of conditions and see how their physical and cognitive behaviour changes. The room can even be cooled to below-freezing temperatures - although that isn’t a problem in modern F1.

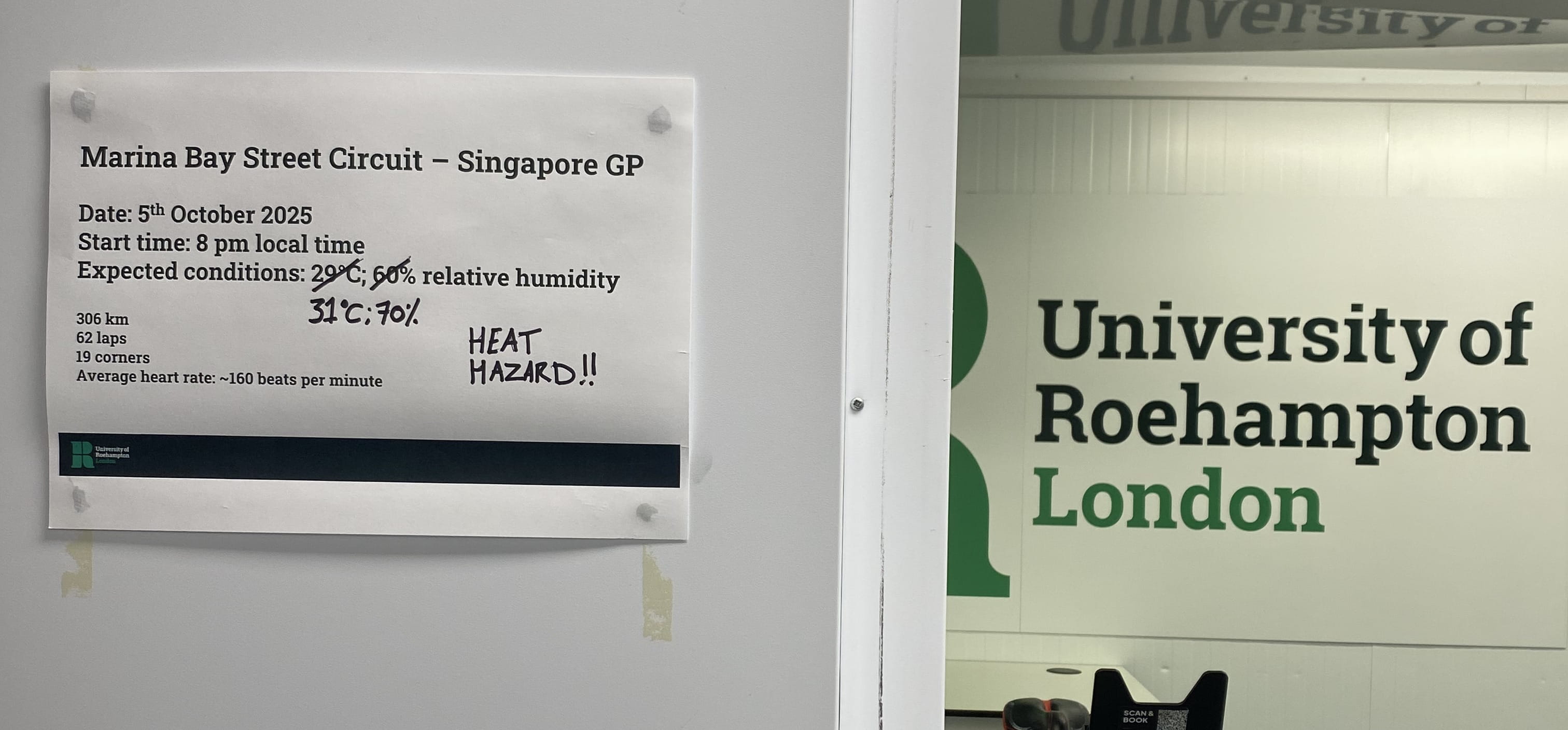

The first ‘heat hazard’ F1 race, as declared by the FIA, was the 2025 Singapore Grand Prix. The heat chamber was therefore set at 31 degrees Celsius with a humidity level of 70% to mimic these conditions.

The door to the heat chamber showing the temperature (31 degrees Celsius) and humidity (70%)

We sent writer Jack Cozens into the heat chamber.

Anything more than a t-shirt and shorts was excessive, while the floor itself was covered in a thin layer of water thanks to the humidity.

First, he had to measure his body mass and attach several thermometers to his body to measure skin temperature.

These thermometers were connected to a laptop inside the heat chamber to monitor his temperature across a period of exercise. He aimed to increase his heart rate to 160 beats per minute - roughly the same as an F1 driver would have during a grand prix - on an exercise bike, while wearing a race suit.

What does it feel like to be an F1 driver?

It’s not long before the athletic reality hits home. One of the thermometers indicates that Jack’s body temperature is actually decreasing rapidly; it turns out sweat has dislodged it from his arm.

As the 20-minute mark passes by - this would be 12 laps into the race - his brain becomes clouded and he begins to find it hard to calculate how many more minutes it would take to simulate a full F1 race distance. That’s five times as much.

The mental fatigue is just as clear as the physical fatigue.

Dr Chris Tyler, Reader in Environmental Physiology at the University of Roehampton (L), and Jack Cozens (R) in the heat chamber

Looking at the temperature charts, Jack’s core temperature is still increasing. Every bit of heat he’s producing is getting trapped in the overalls, just as it would for an F1 driver, and it’s not actually until after the session that he’ll hit peak temperature.

When the final 10 minutes of the session arrive, his heartrate has hit 160bpm and he’s asking the lab technicians to make conversation - any conversation - just to distract his mind from the screen on the exercise bike. What feels like a minute is just a few seconds.

But the end is in sight and, when 45 minutes is reached, Jack cautiously dismounts the bike and takes a second to compose himself.

He says it’s no wonder that drivers have struggled to exit their cars after particularly hot races such as the 2023 Qatar Grand Prix. His chosen adjective - “unpleasant” - is an admitted understatement.

Jack admits that it’s hard to comprehend just how difficult it is to spend 45 minutes in such intense heat while wearing a race suit. A helmet, gloves, fireproof underwear and a HANS (Head and Neck Support) device would prevent even more heat from escaping.

From the perspective of the media, it’s easy to understand why F1 drivers might give terse, even emotional, answers to broadcasters and journalists after the race. After all, they’re whisked to face the media almost immediately after they exit the car and weigh themselves.

Ferrari’s Charles Leclerc sprays himself with water ahead of the 2025 United States Grand Prix

It’s also simple to see why more mistakes could occur in such intense conditions during the race itself.

The numbers tell a more comprehensive story. In the space of 45 minutes, Jack has lost 1.232 litres of fluid and a full 1kg of weight - 1.5% of his starting mass. That cannot be extrapolated linearly but a grand prix driver is expected to lose around 2-3% of their body mass over a race.

His core temperature increased by 1.4 degrees Celsius, to 38.9 deg C, by the end of the session.

Dr Chris Tyler, Reader in Environmental Physiology at the University of Roehampton and adviser to athletes including F1 drivers tells us that this experience tallies with what many racing drivers across multiple series face.

What does this heat chamber experience tell us about F1?

Dr Tyler maintains that understanding the strain that heat and humidity take on athletes is crucial to unlocking performance.

He admits that many spectators and figures might not see the benefit in making F1 easier on top-level drivers - but offers a counterpoint.

“Some commentators and drivers want this to be the most gruelling experience it can be,” says Dr Tyler.

A cooling vest sported by Charles Leclerc at the 2025 Singapore Grand Prix. Water is piped around the driver’s body to cool their skin temperature

“The easy argument as to why people might care is that we know heat impairs physiological, physical, and cognitive performance. You want the best drivers in the world to face the most gruelling conditions, but without a detrimental effect on performance.

“You want them to be separated by fine margins rather than errors or mistakes. There is a health issue - they are humans, and so in certain situations we want to make sure they’re not under undue risk in activity - but a slight reduction in physiological strain should result in improved performance.”

Dr Tyler adds that other sports such as football, athletics, long-distance running, tennis and more have worked to mitigate heat strain but F1 might be lagging behind - which is why the aforementioned 2023 Qatar Grand Prix might have come as a shock to the drivers, teams, and governing body itself.

Now, F1 has stepped in to allow drivers to don cooling vests that channel cold water around the driver’s body - with an increased weight allowance from 800kg to 805kg - for races declared as heat hazards. Singapore was the first one; Austin was next; and this was all sparked by brutal conditions in Qatar.

Given our experience in the heat chamber, it’s clear just how essential these measures are.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)