Car

12 of the biggest innovations in F1 over 75 years

by George Wright

5min read

From the roar of front-engined brutes that ached for grip and spat out oil at the dawn of the world championship to today’s planted, computer-enhanced, turbocharged Formula 1 cars with meticulously sculpted aerodynamics, F1 has always proven a crucible of innovation.

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

The 1950 Alfa Romeo 158, which won the very first world championship race: the 1950 British Grand Prix

1. 1954: Direct fuel injection

With nine wins and 17 podiums from 12 races, the dominant Mercedes W196 cars of 1954 and 1955 took F1 to a new level.

The engines - 2.5-litre straight-eight power units - featured direct fuel injection, nozzles that spray fuel straight into the cylinder.

Direct fuel injection gives quicker and more precise control over the fuel supplied to the engine’s combustion chamber, improving power, response and fuel mileage.

Thanks to these advantages, fuel injection would quickly become the standard in F1 engines, and is now a mainstay of roadcar engines.

The Mercedes W196 incorporated direct fuel injection for the first time in F1, to great success

2. 1958-1960: Rear-engine revolution

Early Formula 1 cars placed their heavy, bulky engines at the front of the car, which negatively affected handling as the centre of mass would be placed too far forward.

Pre-war racing manufacturers such as Auto Union had experimented with placing the engine behind the driver to some success in the 1930s, but the idea lay dormant until Cooper Car Company revived it in the 1950s.

Cooper’s Stirling Moss won the first race for a rear-engined car at the 1958 Argentine Grand Prix, and the superior weight distribution and handling provided by the arrangement soon propelled Jack Brabham to back-to-back world championships in 1959 and 1960.

The way forward was clear, and despite the protestations of the likes of Enzo Ferrari, who famously quipped that “the horse should pull the cart, not push it”, almost all F1 cars since have featured rear-mounted engines.

The Cooper T45 ignited F1’s rear-engined revolution

3. 1962: Monocoque chassis

In Formula 1’s early years, cars were constructed using an internal network of rigid tubes called a spaceframe.

This gave the car the necessary strength and stiffness to resist the forces of racing, and could be covered with a simple aluminium skin to reduce drag.

However, in 1962 this conventional wisdom was turned on its head when Colin Chapman introduced the concept of the monocoque (single shell) to Formula 1.

In this arrangement, there was no separate frame, with the aluminium shell itself providing the structure of the car.

This saved weight, and actually made Chapman’s Lotus 25 even stiffer than rival machines. Space frames as a whole were quickly abandoned, and F1 cars continue to follow the monocoque construction principle to this day.

The Lotus 25 pioneered F1 with a monocoque chassis

4. 1967: Fully-stressed engine

While the introduction of monocoque chassis did away with full spaceframes, the weight of the engine and gearbox still required them to be supported by additional framework—either in the form of a tubular subframe or a strengthened section of the monocoque.

As far back as 1954, however, designers had realised that it was possible to use the engine itself to form part of the structure of the car. This idea had been implemented on the 1954 Lancia D50, but had been largely forgotten in the years that followed.

In 1967, however, Lotus resurrected the concept with the Lotus 49. That car’s Ford DFV power unit was specifically designed to withstand being used as a structural component, and was simply bolted to the back of the chassis, with the gearbox and rear suspension in turn being bolted to the engine itself.

As with transitioning to a monocoque chassis, using the engine to form the structure of the rear of the car saved weight, which has meant that stressed engine construction has stood the test of time.

5. 1968: Aerodynamic downforce

Among the single most pivotal innovations in the history of Formula 1 was the use of downforce-generating wings. The Lotus 49B was the first rear-winged F1 car, sporting the device at the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix.

Teams realised that, by incorporating aerofoils onto their car similar in shape to an inverted aeroplane’s wing, the car would be physically forced towards the track surface, providing improved grip and higher cornering speeds.

Early wings were mounted to the suspension uprights so their downforce acted directly on the wheels, and were mounted high up to keep them out of turbulent air.

However, a series of failures led to a mandate that all wings be affixed to the car’s bodywork going forward.

Nevertheless, development of wings continued unabated, and they have since become an integral part of not just F1, but almost every major motorsport category.

The Lotus 49B brought rear wings to F1 - although they soon had to be mounted to the chassis for safety reasons

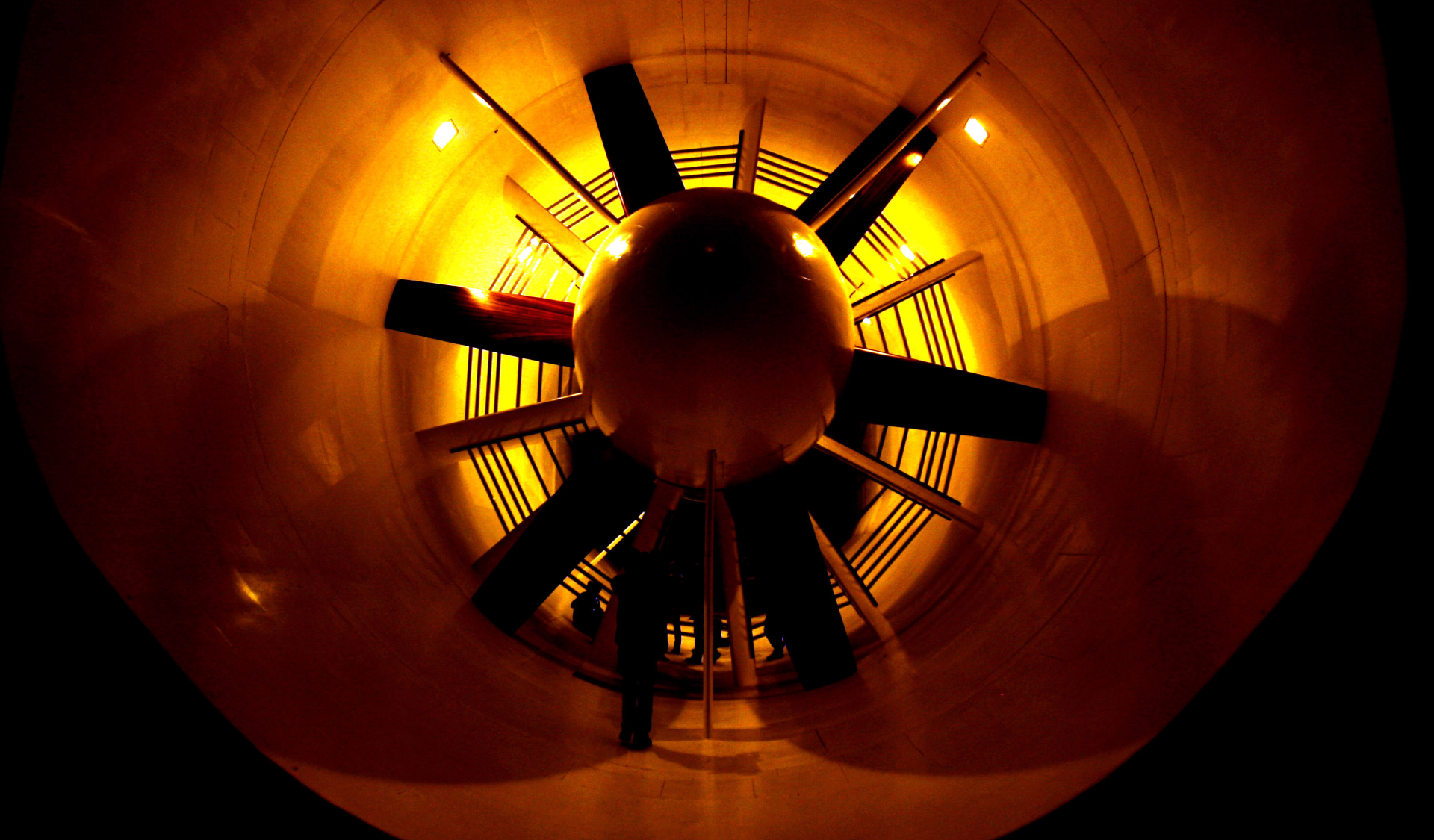

6. 1977: Ground effect

Just under a decade after the concept of downforce had first been introduced to Formula 1, the world of racing car aerodynamics was once more turned on its head.

This time, the revolution depended on a phenomenon called the Venturi effect, where a fluid (such as air) flowing through a constriction experiences an increase in speed but a drop in pressure.

By shaping the underside of an F1 car to form such a constriction (known as Venturi tunnels), and using floor-rubbing side skirts to seal the area under the car off from high-pressure air, a low-pressure zone under the car could be created, which provided massive downforce at the cost of very little drag compared to traditional aerofoils.

Lotus aerodynamicist Peter Wright was the first in F1 to realise this, and the 1977 Lotus 78 triggered a revolution when its secret was discovered. By 1979, every team in Formula 1 had introduced a car which took advantage of ground effect, and the cars of 2025 follow the very same principles.

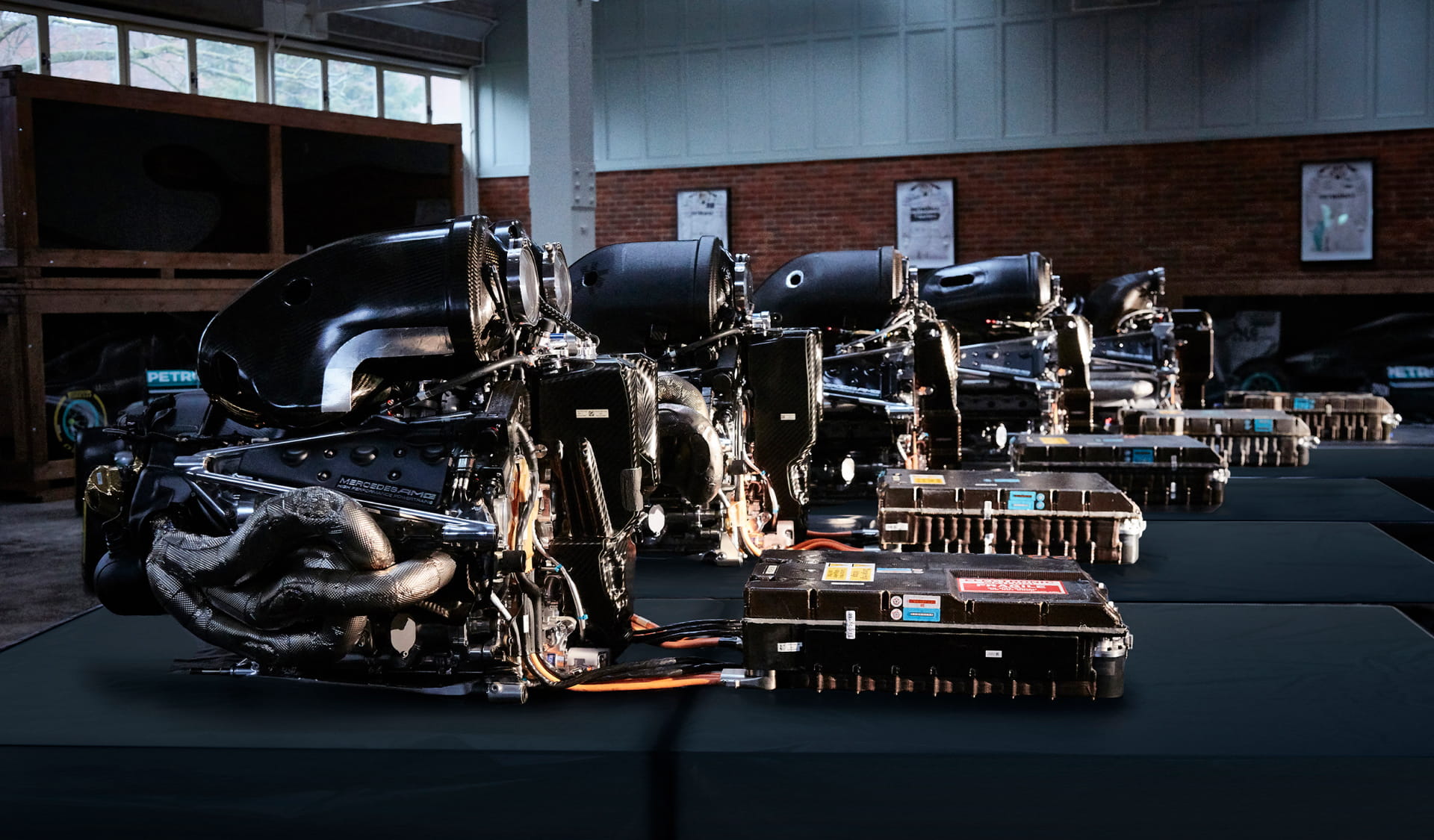

7. 1977: Turbocharged engine

When F1’s regulations switched from allowing 1.5 litre to 3 litre engines in 1966, the new rules included a provision which allowed engines of the old capacity limit to be supercharged or turbocharged and continue competing.

Nobody thought anything of this rule until 1977, when Renault took advantage of the provision to field F1’s first turbocharged engine. This used an exhaust-driven turbine to power a compressor, which pumped extra air into the engine, theoretically increasing power.

The car proved unreliable initially, but continued development turned the engine into a winner.

By the mid-1980s a bevy of manufacturers had jumped on the turbocharging bandwagon, and power outputs had reached over the 1,000 horsepower mark. While this arms race led to higher cornering speeds and turbocharging being banned in 1989, the technology returned to F1 in 2014, and has remained in the sport ever since.

Renault brought the turbo era to F1 with the 1977 RS01

8. 1981: Carbon fibre monocoque

So effective was the monocoque chassis that it barely evolved between its debut in 1962 and 1980.

McLaren changed that with its 1981 MP4/1. This car, designed by John Barnard, featured a full carbon-composite monocoque, manufactured by United States-based firm Hercules Aerospace.

Barnard chose carbon fibre because it promised a staggering increase in stiffness compared to the traditional aluminium monocoque, and was therefore ideal for resisting the staggering downforce generated by ground effect.

The car faced early criticism that it might be unsafe in the event of a crash due to concerns over impact resistance, but these were silenced when driver John Watson had a 170mph crash at Monza and walked away unscathed. After a brief transition period, all F1 cars have since featured monocoques formed from carbon fibre.

9. 1983: Active suspension

Of all the technologies which typified early 1990s Formula 1, active suspension is perhaps best remembered, as it foresaw the powerful influence of computers in F1.

A computer and a series of hydraulic actuators in place of conventional springs and dampers allowed F1 cars to dynamically adjust in response to track features such as corners, bumps and undulations. This made it possible to maintain a constant ride height for optimum downforce, and almost completely negate pitch and roll under braking.

The concept was first deployed in F1 by Lotus in 1983, but it was the Williams team who enjoyed the most success with active suspension after beginning its own development programme in 1987.

After winning two dominant world championships with the technology in 1992 and 1993, active suspension was banned along with a raft of what the governing body termed ‘driver aids’.

The Williams FW14B wasn’t the first car to use active suspension, but it was the first F1 car to win the championship with the technology

10. 1983: Blown diffuser

Blown diffusers are a technology most commonly associated with the early 2010s, but their genesis actually occurred following rule changes in 1983, which banned ground effect via a rule that mandated flat floors between the front and rear axles.

Since the area behind the rear axle was one of the few parts of the floor still permitted to be aerodynamically shaped, diffusers were always likely to be important in a post-ground effect F1.

Renault aerodynamicist Jean-Claude Migeot conceived a way to amplify the diffuser’s effect by channelling high-speed air from the exhaust and turbocharger wastegates through the diffuser. This led to a greater drop in pressure due to the Venturi effect, and generated an extra 80 kilogrammes worth of usable downforce.

After introducing the concept at the 1983 Monaco Grand Prix, Renault won three races using the technology, and just missed out on that season’s world championships.

The concept would then be resurrected by the likes of Red Bull under technical guru Adrian Newey, with 2011’s RB7 proving a particularly potent example of the benefits of using exhaust gas to accelerate airflow through the diffuser.

The 1983 Renault RE40 brought the blown diffuser to F1

11. 1989: Semi-automatic gearbox

Teams had long dabbled with technologies to enable faster or more reliable gear changes throughout F1 history, but Ferrari was the first to fully commit to such a system under the stewardship of technical director Barnard.

The 1989 Ferrari 640 featured a hydraulically-operated gearbox which could change ratios with a flick of a paddle on the steering wheel.

Barnard’s main motivation for making this leap was actually more about aerodynamics than the gearbox itself. Actuating the gears using hydraulics with electronically controlled valves eliminated the need to run a bulky physical gear linkage to the back of the car from the cockpit, and also meant the cockpit could be packaged tightly.

Ferrari struggled with making the system reliable initially, but its benefits soon became apparent. Not only did the semi-automatic gearbox enable superior aerodynamics, but it also made for faster gear changes and even reduced engine failures by making it impossible to “buzz” the engine by changing into the wrong gear at excessive RPM.

With such advantages in mind, by 1996, every team in F1 had followed Ferrari’s lead and they never looked back.

The 1989 Ferrari 640 debuted the semi-automatic gearbox, now a mainstay of F1

12. 2009: Double diffuser

Sweeping regulation changes in 2009 aimed to slash the downforce generated by Formula 1 cars in the hopes of improving racing.

As it turned out, several teams uncovered a loophole in the rules which allowed them to essentially have two diffuser sections stacked on top of each other at the rear of the car.

This enabled the teams to negate much of the anticipated loss of downforce brought about by the rule changes.

After initially being discovered by an engineer at Honda’s junior team, Super Aguri, the idea permeated to Toyota, Williams and most prominently Brawn GP.

While other teams protested the development at the 2009 season-opening Australian Grand Prix, the double diffuser was deemed legal and every team had developed its own solution by the end of 2009.

The double diffuser led Brawn GP to the championships in 2009

The innovation was banned in 2011, but it delivered one of F1’s greatest upsets as Brawn GP secured the constructors’ title and Jenson Button took his one and only drivers’ title in 2009.

The double diffuser certainly wasn’t the last of F1’s great innovations in the 21st century, but it embodied F1’s fundamental nature as a canvas for some of motorsport’s most inspired engineers.

Each of these 12 innovations represents a step that immortalised a team, engineer, and driver - and transformed F1 into the motorsport as we know it today. As the technology curve flattens, the rate of innovation might seem slower than before, but F1 is still capable of surprising and inspiring.

Just as it has done for the last 75 years.

/fw14b-track-logo2.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)