Event

Inside the unusual F2 and F3 bases at the Monaco Grand Prix

by Samarth Kanal

8min read

The Monaco Grand Prix provides some of the most enthralling scenes in sport given its history with Formula 1 - but a delve into the Formula 2 and Formula 3 paddocks reveals an often overlooked and astonishing technical side to this event.

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

Images and sounds of single-seaters screaming through the tunnel and scampering around the hairpin are indelible and emblematic of Monaco, but, behind the facade of the F1 pitlane, there is a hive of motorsport activity in the FIA feeder championships.

All of this takes place in a city-state of two square kilometres, comparable in size to London’s Hyde Park, smaller than New York’s Central Park, and one where flat land is at a serious premium.

The support series paddocks are therefore located well away from the Circuit de Monaco, which makes for a serious logistical and technical challenge.

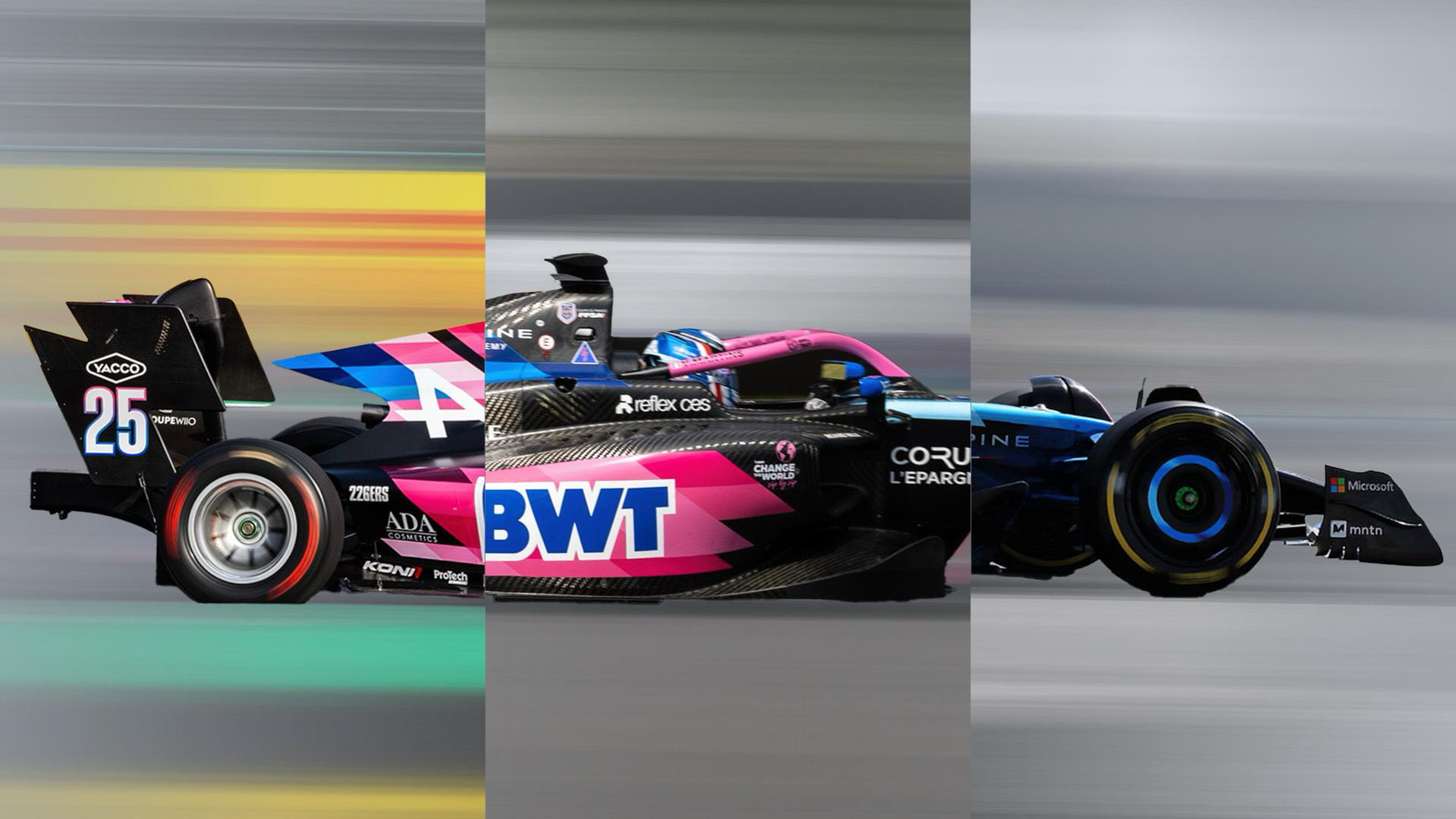

The FIA Formula 3 Championship has raced in Monaco since 2023

The most unusual paddocks on the calendar

Tuesday morning is when the usual traffic of scooters, supercars, taxis and buses is joined by hulking team trucks that navigate gingerly down narrow, sloping streets.

For F2 and F3, this is a delicate and choreographed operation.

“Most of the time, Monaco is back-to-back with another race,” F2 and F3’s director of operations Marco Codello says to Raceteq.

On Tuesday ahead of the race, and a day after the FIA, F2 and F3 infrastructure arrives, F2 and F3 truck drivers and team personnel make their way to their respective paddocks.

“I need to prepare timeslots, because they [the team trucks] cannot come rush all together,” says Codello. They need to respect it, so from one o'clock, two teams, every 30 minutes.”

Team trucks parked snugly inside the Formula 2 paddock at Monaco

Codello faces long days as he conducts the F2 and F3 teams across Monaco, but his work makes for a seamless process.

The 11 F2 trucks arrive in pairs (and a trio) into the top two levels of a multi-storey parking garage - Parking du Chemin des Pecheurs - on the west side of the main circuit. By 5.30pm, the trucks are all parked and lined up with unpacking well underway, water and power mains hooked up.

It’s a tight squeeze horizontally but also vertically; trucks with expandable top decks need to fit under the roof of the ground floor of the parking garage, which isn’t always possible.

The F3 paddock, meanwhile, isn’t even situated in Monaco. Instead, the F3 trucks park and pitch up at the Monte Carlo Country Club, over the border in France and around 2km away from the circuit. F3 teams also have to abide by timeslots to arrive and leave their paddock but on Sunday they have the luxury of time over F2.

All 11 F2 teams must vacate the parking lot as soon as possible after Sunday morning’s feature race to make way for the F1 trucks, as their paddock becomes an overflow parking lot for the F1 teams’ trucks that spend most of the weekend parked on a nearby hill.

The FIA’s scrutineering bay fits neatly into the far end of the F2 paddock

The long journey to the track

Usually, F2 and F3 paddocks are situated close enough to the track - but at Monaco teams are located so far away that they need to plan well ahead to ensure their cars are ready for the upcoming sessions.

Before the engines are fired up for the race, F2 teams have to push their cars for more than a kilometre - through two tunnels, up a hill, and then down a hill through the last corner of the circuit and into the pitlane.

Geoff Spears, team manager of 2024 F2 teams’ champion Invicta Racing, is well-versed in this hillclimb ritual.

ART Grand Prix F2 driver Victor Martins jumping into his F2 car after it has been pushed up the hill outside the F2 paddock. An F1 truck waits on the right-hand side of the road - as it will until the F2 teams depart their paddock

“For me, it's quite normal here because I've been doing this series, in GP2 since 2007, and we've always been in this paddock. So I'm quite used to doing that. But yeah, it is a bit of a push and I’m not being funny; there's not a lot of wind up that hill… and it can often be fairly warm as you're pushing the cars up there and, without the driver, they weigh the best part of 730, 740 kilos.”

It takes three mechanics with one in the cockpit to steer to push the fully-fuelled F2 cars through the paddock with marshals warding off tourists and locals along the way.

“And the best bit is, when we're pushing the cars up, there's often oncoming traffic,” says Spears. “And then the marshals will be like, ‘Oh, you have to stay over to one side!'. But the road's not flat!

The F3 paddock is located at the Monte Carlo Country Club, east of the circuit, in France

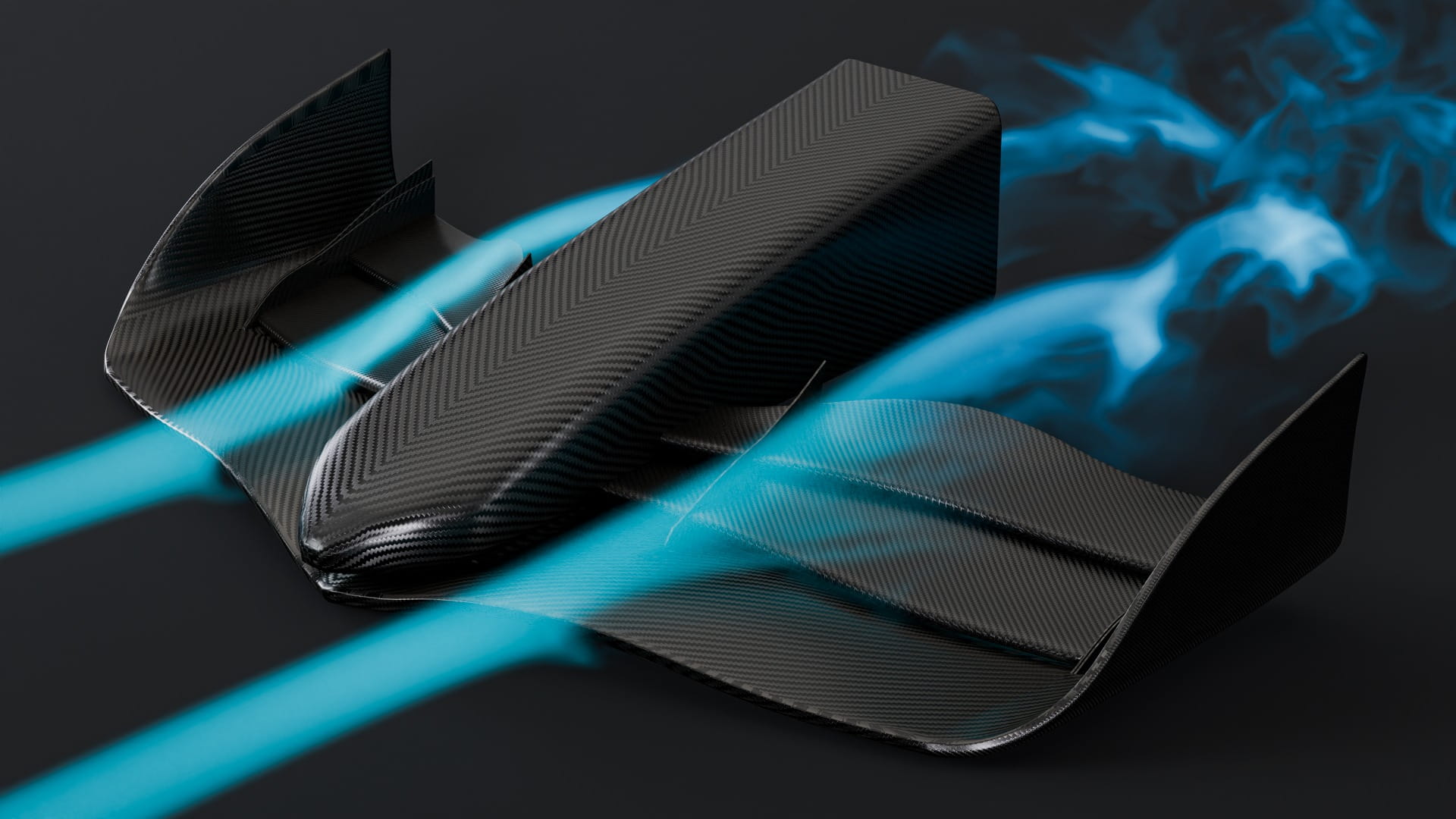

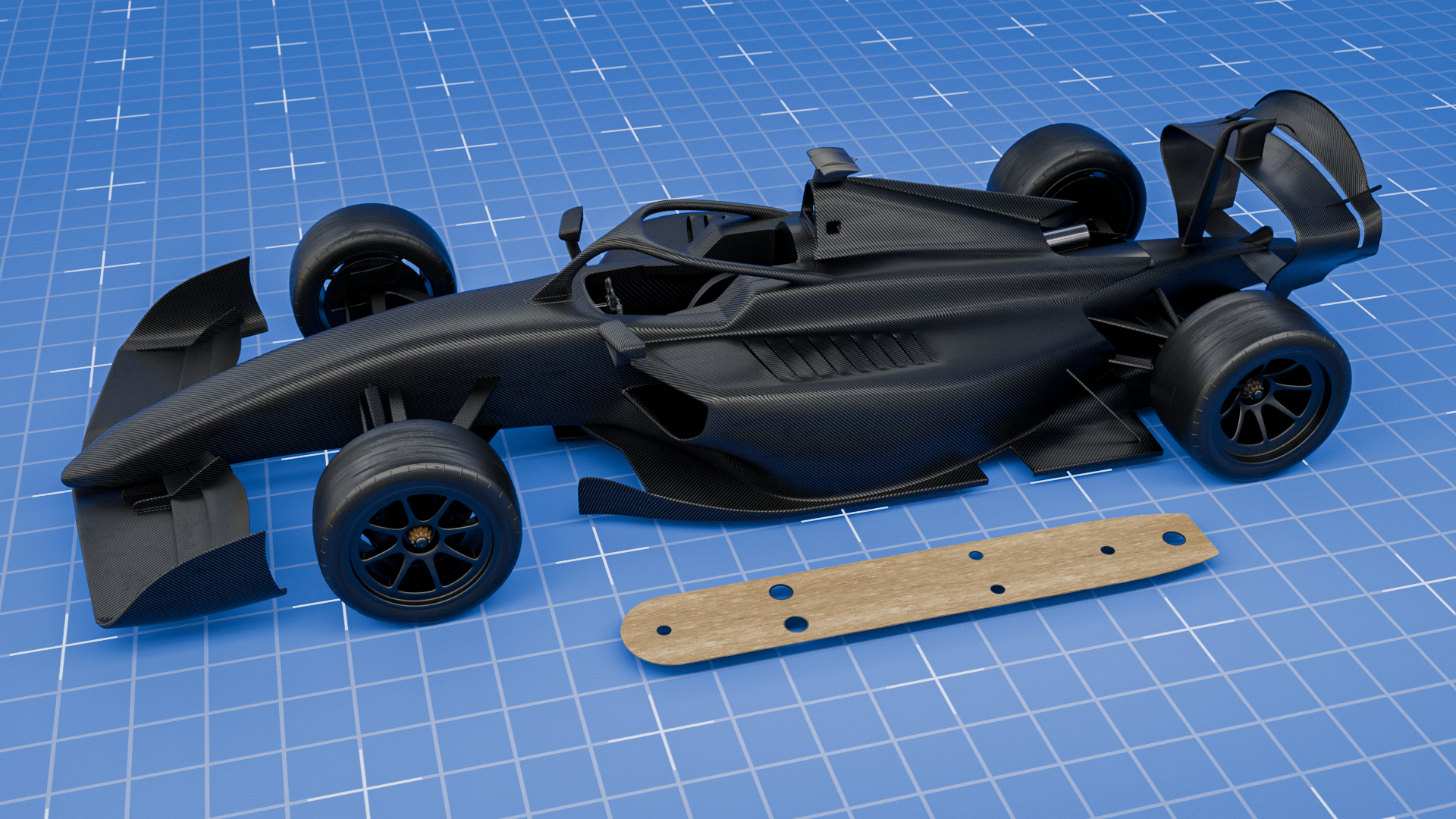

Car, Innovation

What is the plank assembly and skid block and why are they so important in F1 and F2?

“It's got manhole covers and the car is grounding out and there's points where you have to go around them, and they're shouting that you have to go over them. We can’t - we can’t physically push over them. The car’s too long.”

The rest of the necessary gear gets transported to the pitlane using the teams’ quad bikes that lead a long train of trailers with tyres, parts, and tools, often with mechanics and perhaps drivers hitching a ride on the side.

The F3 teams have to contend with a longer journey in and they face much more of the Monaco streets on the way. Marshals play a valuable role in ensuring the drivers, engineers and cars can safely navigate their way through the crowds.

On the return journey, unless they’ve been involved in a crash, the F2 and F3 cars can make their way back into their respective paddocks using their own power - which makes for surreal scenes as parades of single-seaters hum through the streets.

F2 cars take to the streets after their sessions have ended, their V6 engines howling through the various tunnels of Monaco

Dealing with Monaco’s tight confines

The quirks of Monaco don’t stop at parking and logistics.

The pitlane is shorter and narrower than at other circuits, which means teams keep much of their equipment on trolleys inside the pits to avoid it spilling out. When a car comes in to change tyres, it can be a dicier affair than normal.

“It’s more likely that the driver's not going to hit his marks in the pit box because maybe there's a car just coming out, or there's a lot less space between the pit boxes,” says Spears, whose job during pitstops is to signal when the driver can return to the pitlane.

“That means the mechanics are more likely to have to move to do the pitstop quickly. I do the lollipop, which is fairly intense because the pitlane is short and there’s a lot going on.”

Unsafe releases are common - but Invicta chose the last pit box before the exit (having had that choice by virtue of winning the 2024 championship) to minimise this risk in 2025.

The tight confines of the Monaco pitlane mean incidents are likely when drivers come in to change tyres, especially during a race

There’s plenty of traffic on the airwaves too.

Teams generally mount a signal repeater on their respective truck to receive communications and data, but, given the distance between the paddock and the circuit, they often position a portable repeater between the circuit and the paddock to avoid the risk of telemetry and radio dropouts.

Spears explains that radio and GPS reception can still be erratic.

“Definitely through the tunnel, but even a little bit before - so from Turn 5 [Mirabeau Haute] onwards, the radio signal’s not fantastic. So, there's a reasonable chunk of the lap where you struggle to communicate with the driver.”

Race engineers often have to relay a message over the radio to a driver before they reach the tunnel, and repeat it once they exit to ensure they’ve heard it.

“And it restricts you a bit on when you can tell them things so there’s sometimes a bit of a delay between something happening and them getting the information. Worst-case scenario, they hear [the message] twice.”

On a circuit where it’s easy to accidentally block another driver from completing a fast lap during qualifying or practice, race engineers have to keep a watchful eye on the GPS data to see where their driver is on the circuit and ensure they’re not blocking a rival.

Rodin driver Alex Dunne on the pitwall, from where his engineers relay crucial messages during sessions

This task is made more difficult given GPS dropouts can happen with cars briefly jumping around, or even disappearing from, the track map.

All of this adds to the set-up and driving challenges that make Monaco such a challenging - but covetable - race to win.

The four-day schedule (rather than three) means sessions are a bit more spread out and teams might be able to enjoy a bit of downtime; the draw of Monaco isn’t lost on them despite the other constraints. There’s also the matter of the views from the respective F2 and F3 paddocks: sweeping vistas of the city and the sea.

“We try to have an evening to relax,” says Spears. “It's part of being here, it's not just about the racing, it's about the experience of being at Monaco. That's where having the four sessions over four days is quite nice actually, you're a little more chilled on the schedule, and so we can be a little bit more flexible on their working hours.

“It's still full on. The guys earn their money out of this,” Spears underlines.

The F2 and F3 paddocks are far removed from the main circuit and opulent marina of the Circuit de Monaco, but it’s there that team members and drivers navigate a multitude of obstacles to prepare for one of the greatest spectacles on the motorsport calendar.

It’s despite those obstacles - or perhaps because of them - that Monaco is the race that every driver wants to win.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)