Innovation

£500 and 11,000km - Sergio Rinland's road to designing Formula 1 cars

by Rahil Hashmi

7min read

Travelling 11,000 kilometres from your home country with £500 in your pocket is a difficult decision to make. Yet Sergio Rinland did exactly that in chase of his dream career as a Formula 1 engineer.

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

The Argentinian studied mechanical engineering in Buenos Aires and moved to England in 1980 to work as a mechanic for a small British outfit. That led to a job for Williams, where he was part of the team that designed the 1986 F1 constructors’ championship-winning FW11 - in which Nelson Piquet won the ‘86 and ‘87 drivers’ championships.

"I was completely mad," Rinland admits, reflecting on his move to the United Kingdom. "But I wanted to design F1 cars, and F1 was here."

Rinland also designed the 1987 Brabham BT56, BT58, BT59 and BT60, with a stint at F1 team Scuderia Italia in between.

After working for F1 teams, Rinland established his own design company, Astauto Ltd, which designed the much-lauded but often-forgotten Fondmetal GR02. Astauto folded soon after and Rinland went on to design for Benetton F1 Team, Sauber and Arrows before resurrecting Astauto as a motorsport and automotive consultancy firm.

Now he’s sharing his experience with the next generation of motorsport engineers at Oxford Brookes University while consulting major teams and series.

Here’s how Rinland made it to the pinnacle of motorsport engineering.

Sergio Rinland on the Brabham F1 pitwall in the 1980s

First foray in Formula Ford

After moving to the UK in 1980, Rinland secured a position as a mechanic with a small Formula Ford team known as PRS. Immediately, his skills were put to the test. Tasked with changing gear ratios for a test at British circuit Snetterton, he found himself under team boss Vic Holman's watchful eye.

Rinland recalls: "I knew a lot about gearboxes, but I was scared to drop something! It took me a long time, and Vic kept raising his eyebrow, thinking, 'Who on earth did we hire?'"

During the test session, Rinland spotted a flaw in the design of the car's nose.

"It's got a very nice inlet, but there's nowhere for the air to come out," he explained to Holman. Confident in his team's design, Holman dismissed the concern.

The test, however, proved Rinland right. The car overheated dramatically, reaching a scorching 120 degrees Celsius. Desperate for a solution, Holman turned to Rinland and asked: "So what would you do in that nose to make it cool?"

Armed with a sketch, Rinland proposed a modification, and Holman gave him the go-ahead.

"There's some aluminium and pliers over there," he instructed. "Just get on and do it."

Rinland's modification not only resolved the overheating issue but also improved the car's handling. This impressed Holman, who recognised the talent within his young mechanic.

"He said, 'From tomorrow, you're going to be our designer,'" Rinland recounts.

This marked his first official step into the world of motorsport design.

An example of a Formula Ford single-seater racing car at Silverstone in 2017

Entering the Formula 1 paddock

Rinland's ambition extended beyond Formula Ford. After his stint with Holman, he honed his skills in Formula 2 and Formula 3 with famed racing car designer Ron Tauranac. But it was a visit to the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch, not as a competitor but as a keen observer, that would prove pivotal.

At Brands Hatch, Rinland found himself chatting with Jeff Hazell, the Williams team manager.

“I said ‘I'm working for Ralt in Formula Three and Formula Two, but my ambition is always to get to F1,'" Rinland recounts. Hazell, sensing an opportunity, took Rinland to meet John Macdonald, a key figure at F1 team RAM Racing.

"Jeff told John that he had to give me a chance," Rinland says with a chuckle.

Macdonald was intrigued. This chance encounter led to an interview and, soon after, Rinland found himself working for RAM Racing. The transition to F1 presented new challenges.

"The tyres were enormous!" he exclaims. "I was used to the narrow tyres of F3 and Formula Ford... Suddenly, I'm engineering an F1 car with these massive things!"

The 1980 RAM Racing Williams FW07 with massive rear slick tyres

He quickly learned that in F1, "Everything you design is to the service of those four contact patches. Nothing else matters."

By the end of 1985, Rinland had joined Williams. "I went from the back of the grid to the front," he jokes. Despite the higher stakes, Rinland maintained his focus.

"I can't remember being overwhelmed," he reflects.

"For me, it was just the job, and I went there every morning and did it." This dedication, combined with his growing expertise, contributed to Williams's success, including its championship-winning FW11. Rinland had not only made it to F1, but his expertise was now contributing to race- and championship-winning cars.

Nigel Mansell at the wheel of the Williams FW11 at the 1986 French Grand Prix, where he won ahead of McLaren’s Alain Prost

Taking charge at Brabham and Sauber

Rinland's career continued its upward trajectory with a move to Brabham, led by Bernie Ecclestone. This wasn't just another step; it was a leap into a leadership role.

"Gordon Murray left, and Bernie put the design team in the hands of three people: John Baldwin, David North, and myself," Rinland recalls.

He was no longer just a designer; he was a leader, sharing the responsibility of shaping Brabham's future. The team operated with a clear division of labour: Rinland focused on the car's core structure - the monocoque and suspension - while David North tackled engine integration and aerodynamics, and John Baldwin handled the gearbox.

But just as he was finding his feet at Brabham, an unexpected opportunity arose. Dallara came calling, offering him the chance to lead its F1 project with Scuderia Italia.

"That was my first job as chief designer," Rinland shares.

The Brabham BT59, which was chiefly designed by Sergio Rinland and Hans Fouche

Stepping into this role wasn't just about technical drawings; it was about managing people, personalities, and expectations.

"You have to learn how to delegate," Rinland explains, "and how to make sure that everyone has the knowledge they need to excel."

It was a course in leadership, testing his ability to guide a team towards a common goal. Rinland thrived in this leadership role. He returned to Brabham as chief designer, overseeing the creation of iconic cars like the BT58, BT59, and BT60.

He worked for Benetton F1 Team from 1996 until 1999 before becoming Sauber’s chief designer. At Sauber, he orchestrated a remarkable turnaround, leading the team to a fourth-place finish in the 2001 world championship.

"That car went from eighth to fourth and achieved podiums the team had never seen before," Rinland proudly recalls.

The 2001 Sauber C20 took the team to fourth in the championship

Sharing the wisdom

Today, Rinland's influence extends beyond the drawing board and the windtunnel. As owner and managing director of Astauto, an engineering and management consulting company, he lends his engineering skills to a variety of clients.

He also lectures at Oxford Brookes University, sharing his decades of experience with aspiring motorsport engineers.

This mentorship role is something Rinland clearly values. When asked about the advice he gives to his students, he doesn't hesitate: "Read history."

He expands on this, explaining that understanding the past is crucial to avoiding repeated mistakes.

"If you read history," he says, "you learn what mistakes other people made, and you don't make them yourself. "

Rinland's passion for motorsport remains evident in his views on F1 regulations. He advocates for rules that encourage creativity and innovation, drawing parallels to those employed by Le Mans. He argues that regulations should focus on outcomes rather than overly prescribing design solutions.

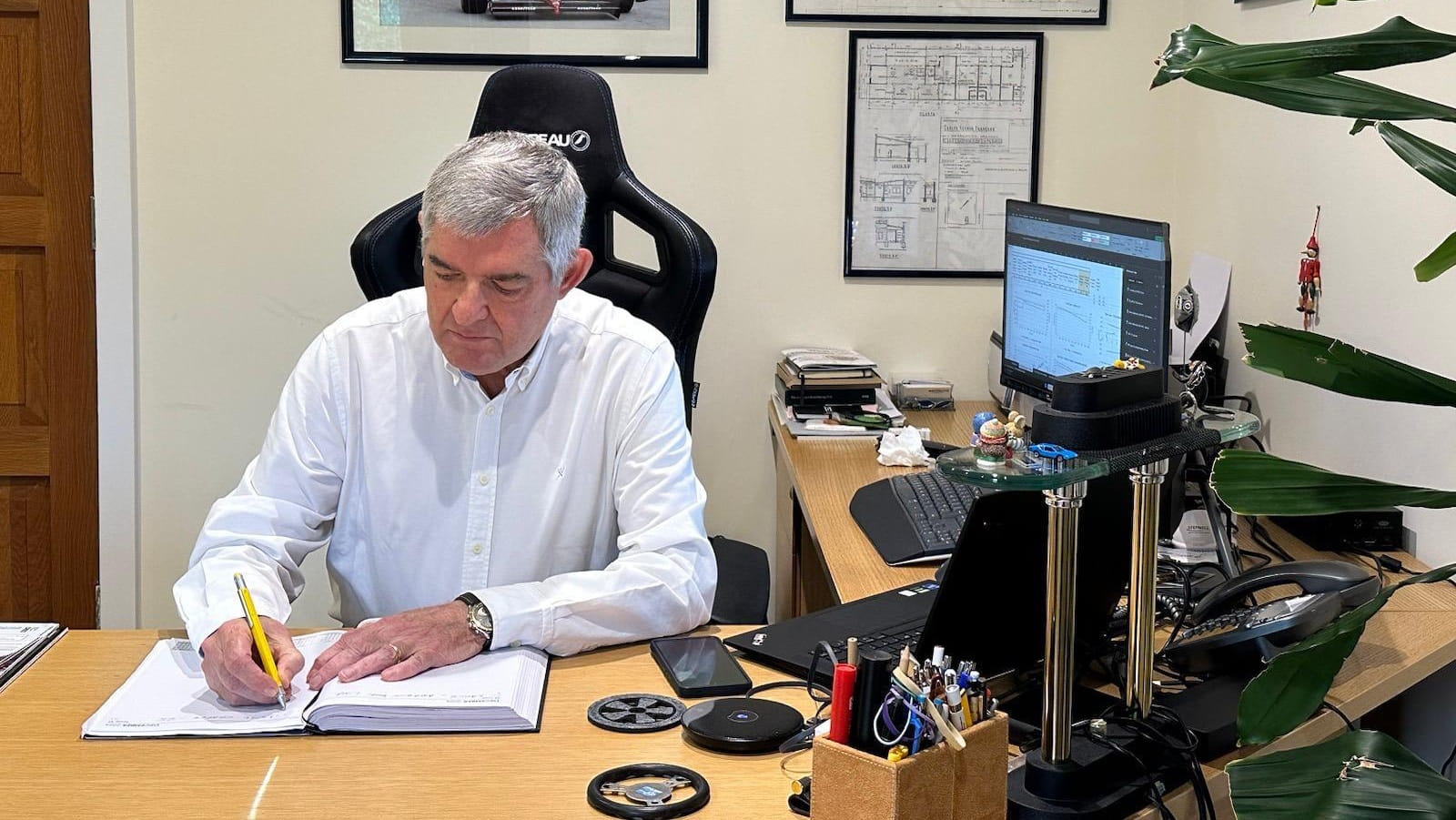

Sergio Rinland in his design office, in front of a photograph of the 1988 Scuderia Italia F188

"Instead of allowing engineers creativity to achieve a certain goal, they give them the goal," he laments.

"I don't like those kinds of regulations."

To illustrate his point, Rinland uses a compelling analogy: imagine trying to control the flow of a river. Restricting it at its source, he argues, is like having overly prescriptive regulations.

Instead, he suggests controlling the flow at the river's mouth, allowing for variations upstream while ensuring the desired outcome downstream. This, he believes, is how F1 regulations should function, setting performance targets while allowing for a wider range of design solutions.

In his final piece of advice, Rinland emphasizes the importance of networking. "You have to build your portfolio of contacts," he advises.

"Never feel afraid. Knock on the door 25 times. And if they close the door 25 times, go knock on the door again."

He encourages young people to reach out to their role models in the industry, stressing the importance of seeking

guidance from those who have already navigated the path to success.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)