Car

Dan Fallows: Why the F1 2026 launch renders don’t match the real cars

by Dan Fallows

7min read

Formula 1 fans relish launch season. After the lull of winter break, 3D renders of F1 cars featuring new sponsors, paint jobs and new bodywork are a welcome excitement. But, as you might have noticed, they usually don’t match the photographs we’re served from shakedowns and pre-season testing…

Sign up for a newsletter and we'll make sure you're fully up-to-date in the world of race technology

It’s all part of a carefully curated and sculpted pre-season media effort by F1 teams. Not only do sponsors have a say in what goes out to the general public, but aerodynamicists and engineers do too.

In recent years, these preseason events have been known as livery launches rather than car launches. Teams reveal show cars with an updated livery based on the previous year’s car. It’s an easy way to avoid showing details of the new car without disappointing sponsors.

Of course, with 2026 being a big regulation change, the car models have had to be updated extensively.

The car models we have been shown in this year’s livery launches don’t have to be compliant with the technical regulations, but they will probably look indistinguishable from a fully legal F1 car - at first glance. And that is an important point: for anyone wanting to keep details secret for as long as possible, the launch renders will need to be indicative rather than accurate.

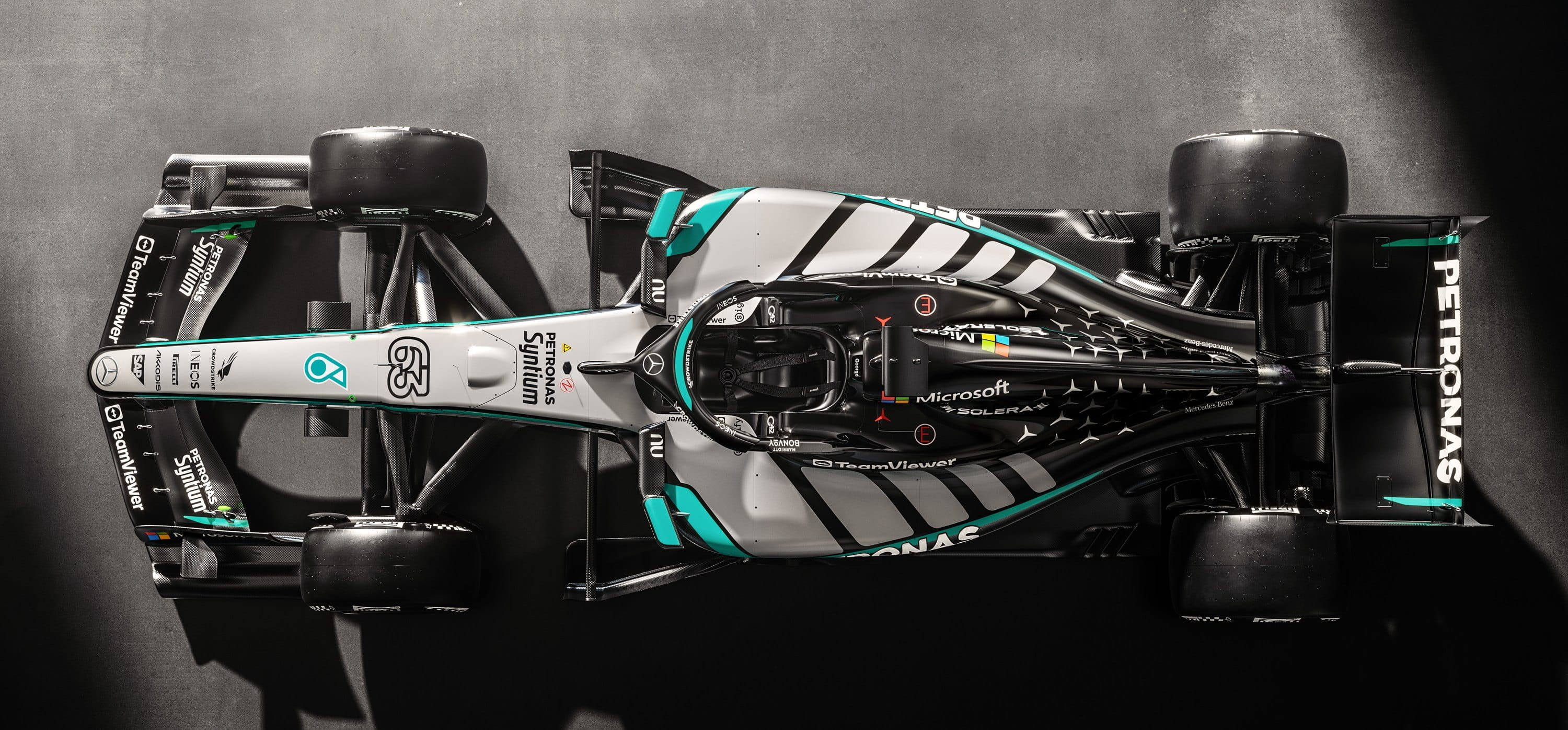

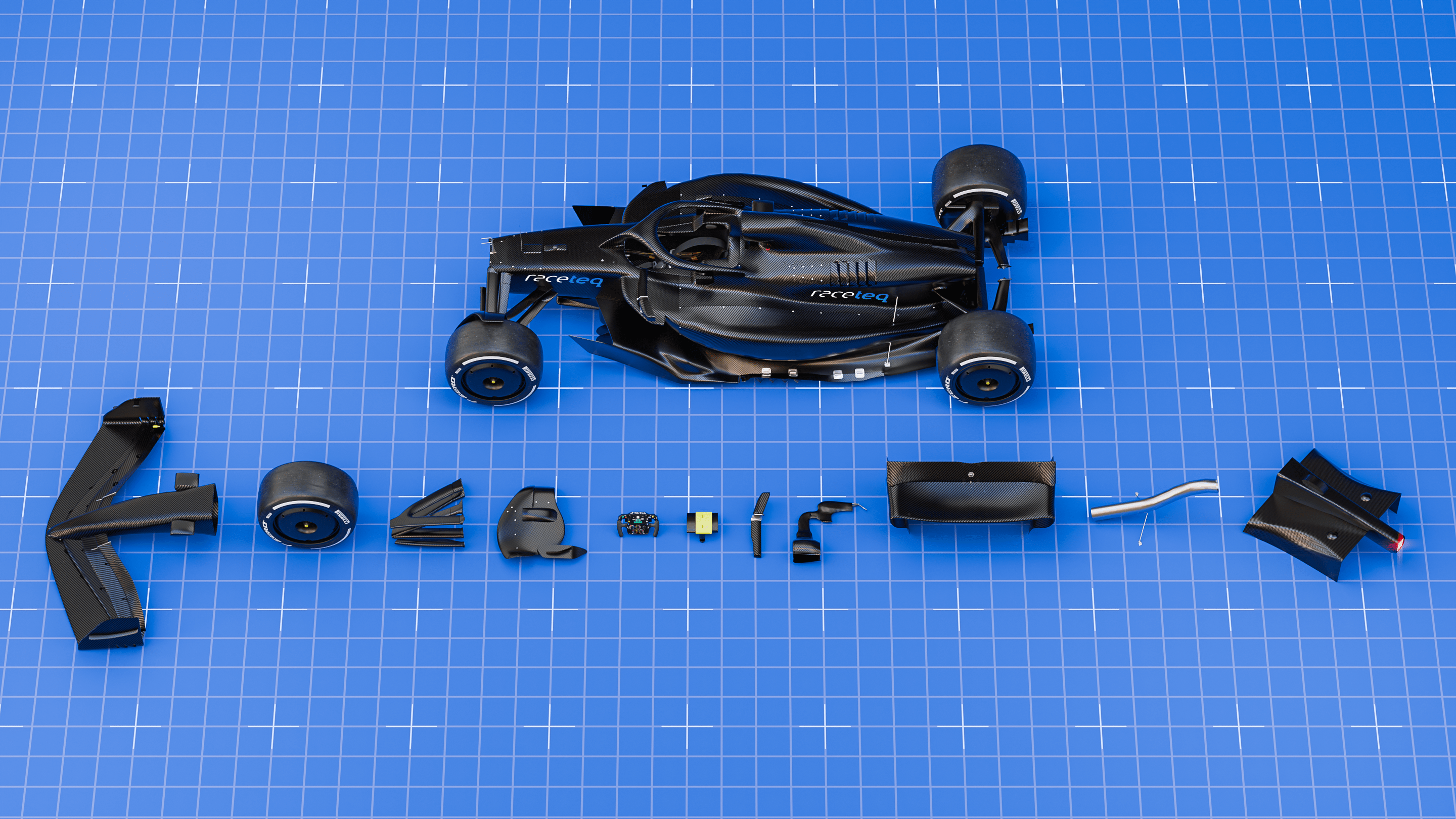

A top-down 3D render of Mercedes’s W17 F1 car. Launch renders are seen as indicative rather than accurate, but they can still prove useful to rival aerodynamicists

In order to provide adequate marketing materials, a 3D model of the car is normally created, sometimes directly from the CAD (computer-aided design) files used to make the real car, and digital artists will then apply the livery.

If that model is accurate, it would be a very useful resource to a rival team if it were to fall into the wrong hands. I have normally taken the approach that once a model like that exists, it is very difficult to track what happens to it. Bearing that in mind, it makes sense to ensure the launch model is not entirely faithful.

Williams highlighted these dangers when it planned an augmented reality app for the release of its 2021 car, the FW43B. Before the launch, the app was unpacked by someone and the 3D model of the car was extracted.

Whoever did this made it available online, albeit briefly, and the car model was widely distributed within minutes. I can say definitively that no rival team would have allowed the files onto their systems. Apart from not wanting to be in possession of another team’s intellectual property, it would have been entirely immoral to do so.

Even something as innocent as an overhead view of the exact car can prove extremely useful to a rival team. If a marketing shot is taken from above, it is often easy to find fairly accurate wheelbase values, for example, after which the location of several key components can be measured. Back in 2022, when Mercedes emerged with its unusually slim sidepod inlets, it was only through understanding where the chassis sat relative to the wheels that we could understand the loophole in the regulations it had found. A clear overhead render of the exact car makes pinning down these dimensions very easy.

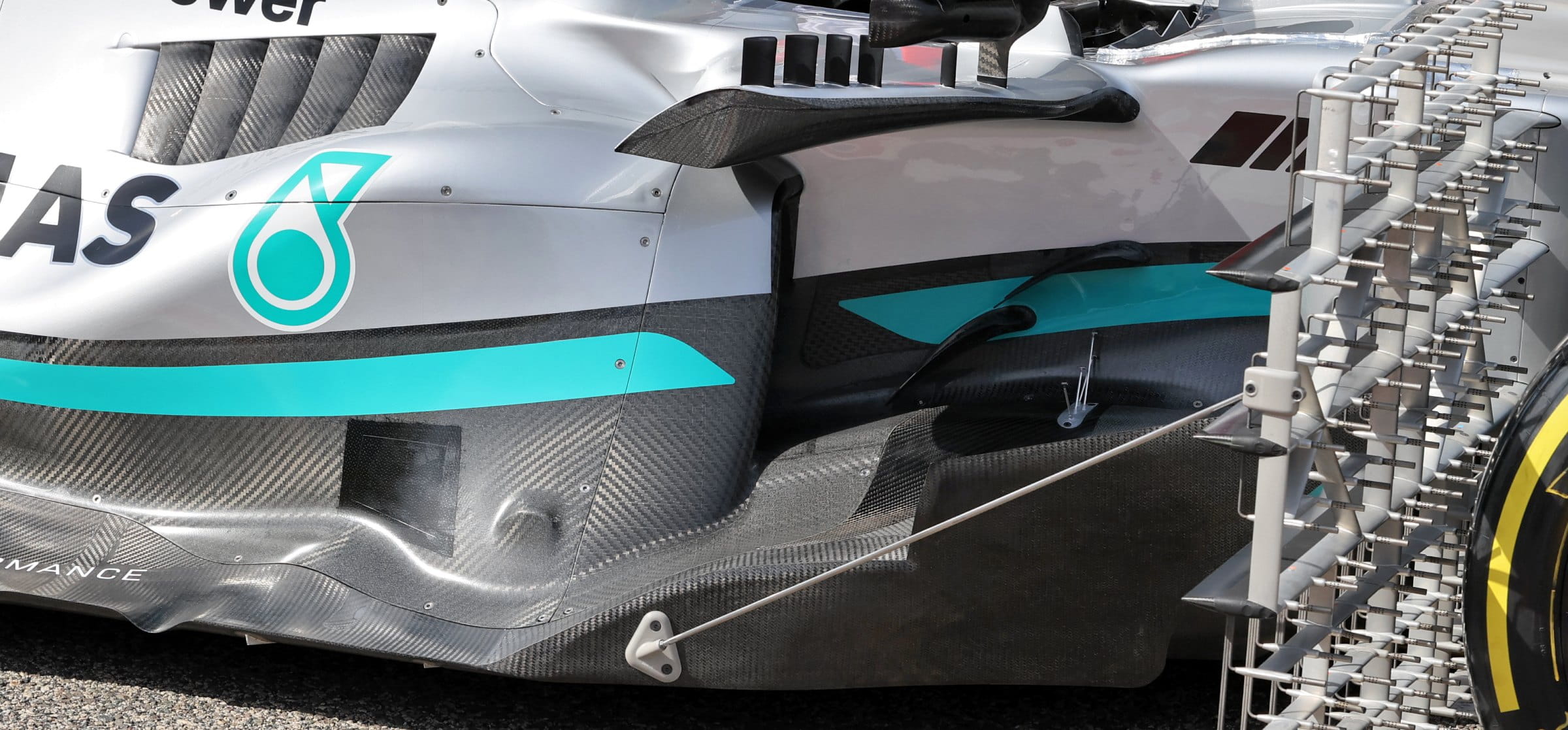

Mercedes shocked rival aerodynamicists, fans, and journalists, with its slimline sidepods in 2022 F1 preseason testing

There are several ways of avoiding this problem, the simplest of which is to not show the launch car at all. Digital artists can take the approximate dimensions of the real car and come up with a stylised version, built from scratch, which will be suitable for showing the new livery, but bear no relation to the car at all. I take the view that this is a bit of a shame for the fans.

While it is understandable that key parts of the car should be hidden from view for as long as possible, it is kinder on the fans to show a reasonable representation of what they will be supporting on track.

To that end, another option is to make some judicious alterations to the CAD model of the real launch car. In the past, I have asked a good surface artist to make changes that are difficult to spot, but which are enough to mean the model is no longer accurate.

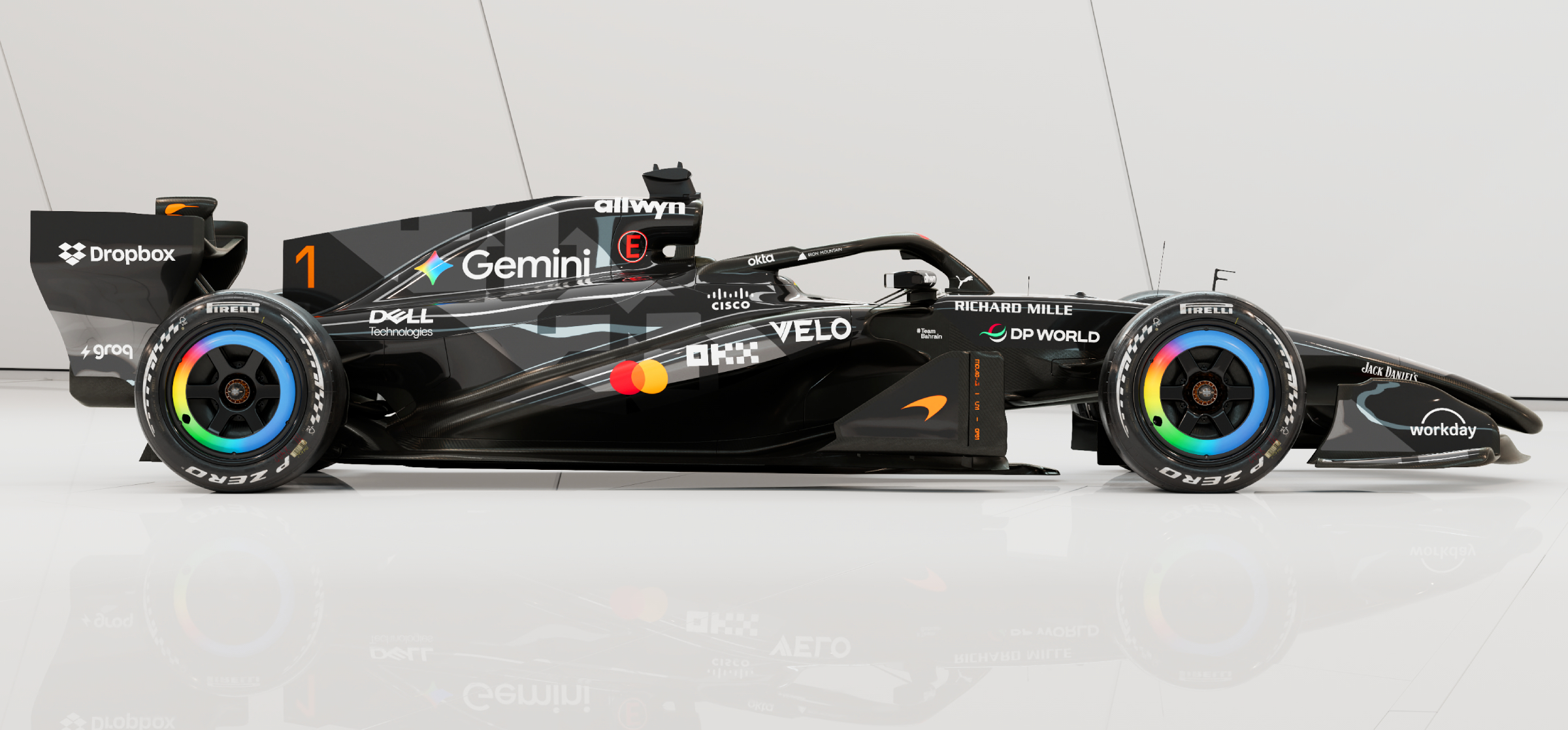

The 3D model that McLaren used to show its 2026 F1 testing livery was remarkably simple

Typically, these would include removing parts that are not going to be shown, stretching key areas such as the floor, and making subtle changes to the wings. The end result is likely to fall foul of the regulations but, as long as the transgressions are subtle, no one should be left disappointed.

The added advantage of this is that if any technical partners would like a 3D model for their own marketing purposes, they can be given access to the modified version without fear of losing control of valuable intellectual property. I have even known these models to be used as the basis for F1 videogames and diecast models.

For teams wanting to confuse their rivals, launch pictures offer an opportunity to add in some odd or controversial features. Although every team knows not to trust livery pictures, they will still look at them, offering a chance to add some geometry that will cause a commotion.

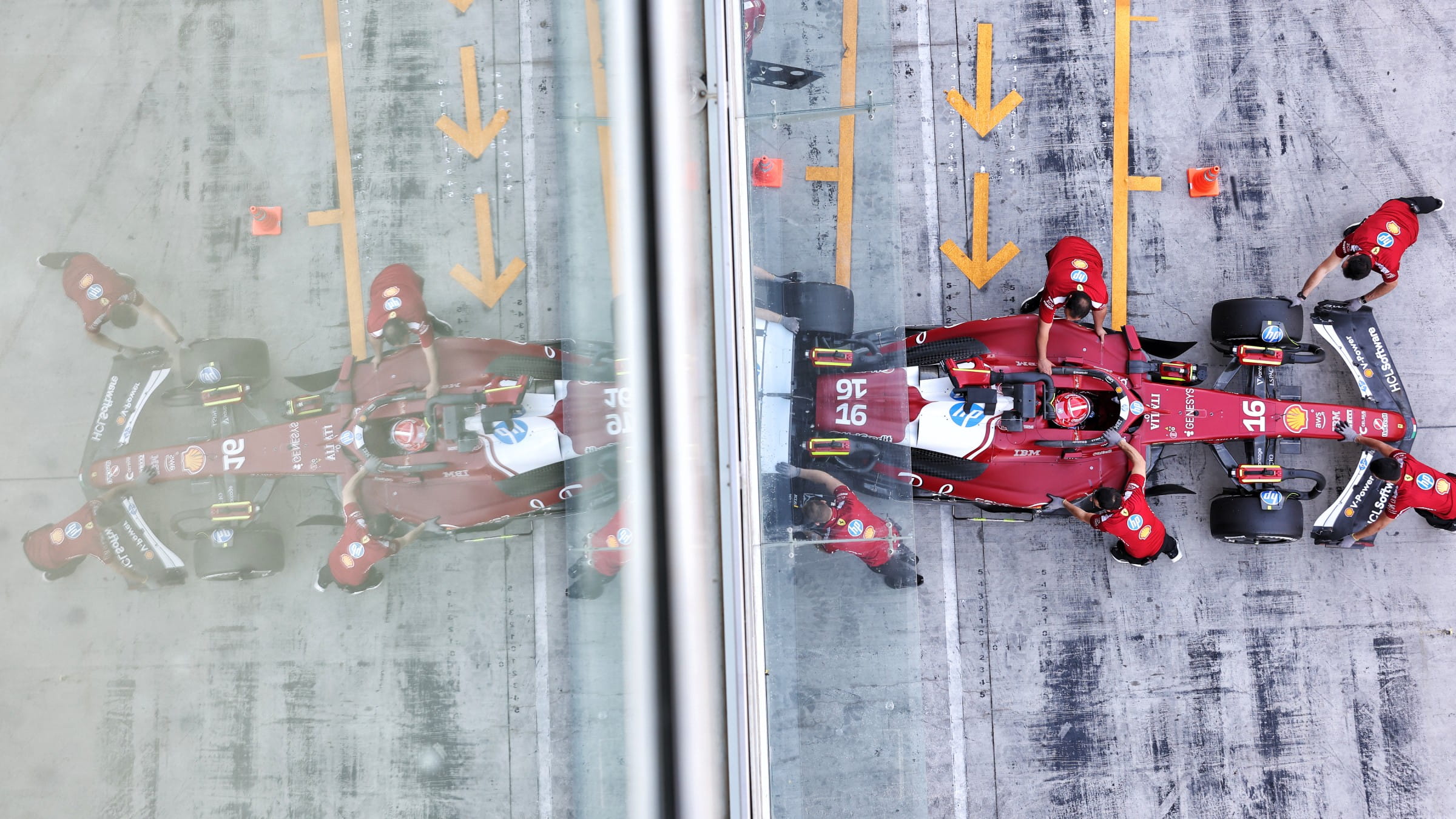

Memorably, Alfa Romeo did this in 2023 when it presented its launch car with multiple vanes along the outboard floor edge, well past the legal limit for doing so.

Alfa Romeo threw out a red herring in 2023 as the floor of its F1 car sported multiple vanes

This caused short-lived consternation from many of the teams, who wondered if it had found a regulatory loophole. The simple answer was that they had not, and the car that eventually ran was back to having a more conventional (and legal) design.

In the past, I have often had to sign off on the pictures released to the press of the launch car. Occasionally, those renders can have strange artifacts of lighting, or come from angles which seem to show parts that are not there.

Normally I would prefer those to be released, as they may have thrown our competitors off the scent, even if briefly. Any attention focused on rogue or non-existent geometry is time taken away from the parts you would rather they ignored.

If you think you have something innovative on the car, the longer you can keep that hidden, the better. Car development is a race, and the later someone starts developing a version of your clever bodywork or system, the longer it will take them to catch up.

So the purpose of launch pictures, and the digital model they are based on, is simply to give a reasonable idea of how each team’s car will look and to show off the new livery. If the key details of the car can be hidden, so much the better.

The 3D renders will live on past reality and continue to be used for promotional materials, being immortalised in the form of the aforementioned model cars and videogame models.

Crucially, they spark the excitement and anticipation from F1 fans who have been waiting months for first sight of the new liveries. Behind the skin though, there’s plenty more than meets the eye when it comes to these 3D models.

.png?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)